I’ve written elsewhere about the elusiveness of British culture, this despite having now lived here longer than anwhere else, including my U.S. homeland and France (see Love and Estrangement). In that earlier piece, I returned to key moments that now, looking back, seem part of a gradual recasting of my knowledge and affection when it comes to the UK.

“I can’t help but notice that some subtle shift has occurred - say over the past decade. A realization that, despite my frequent declarations about how utterly incomprehensible England is, some deeper knowledge was forming. Not the knowledge of one born here. Not the deep-set awareness of regions and accents, class slights, post-imperial cruelties, and historical divides. Not the grasp of those stereotypical, grain-of-truth traits we talk about – British reserve, eccentricity, concealed meanings. I have a sense of these, even a competence in many of them, but they remain foreign in my mind.

But yes, such knowledge comes, even if it hides beneath everyday consciousness. And more than that, affection comes. I am now regularly struck by waves of love for the UK. As with America, it is not uncritical, but it is surprisingly committed. It’s a love of landscapes and people. Early friends here and recent ones too. Footpaths in Yorkshire, Devon, Sussex, and Scotland. Walking coastal paths or across downs or moorlands to a country pub. Particular London bus routes and tube lines - the great city in its layered history and glorious diversity. The National Health Service, postwar Britain’s greatest achievement. The BBC, for all its flaws. Labour Party meetings that got out of hand. Pub gatherings after Labour Party meetings that got out of hand.” (Love and Estrangement)

In the piece, I dig up old and seemingly small incidents that mark this changing cultural knowledge and affection, ending with the subject of today’s brief postcard: my first encounter with Bonfire Night - the annual celebration of November 5th and the Gunpowder Plot.1

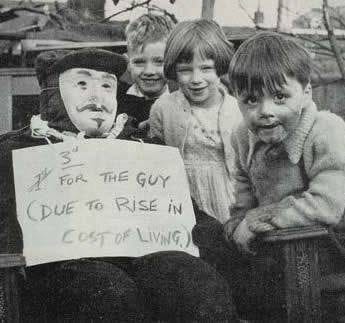

In 1981, not long after moving to the north London neighbourhood of Finsbury Park, I was exiting the tube station when I heard kids’ voices calling out, “Penny for the Guy!”2 And then I saw them, huddled just inside the station entrance on a cold and darkening November night, a homemade ‘Guy’ between them, and an overturned cap for the collected coins. They looked something like this group:

At the time, I knew almost nothing about the Gunpowder Plot or the holiday. I could not have foreseen the changing meanings and traditions or the relative decline of Bonfire night celebrations, although there are places – Lewes, for example – that continue to hold large events, now burning effigies of Trump, Putin, and other tyrannical figures. And yes, fireworks are still heard pounding and crackling during the dark nights of early November, though Halloween now jostles for position as the autumn holiday.

The kids on corners asking for pennies will be lost in time. Yet, that passing encounter of the little group in Finsbury Park during the harsh Thatcher years remains one of the strongest in my recollections of London, and still seems most vividly ‘English’ - a memory of kids, underdressed, feeling the cold, but joyously free for a few hours. Little rebels on London street corners and in the entrances to tube stations.

See, for example, What is the story behin Bonfire Night? Royal Museums Greenwich: “The Gunpowder Plot was a failed attempt to assassinate King James I of England during the Opening of Parliament in November 1605. The plan was organised by Robert Catesby, a devout English Catholic who hoped to kill the Protestant King James and establish Catholic rule in England… English Catholics had expected more religious tolerance under James I compared to the reign of his predecessor, Elizabeth I. However, these hopes were dashed in early 1604 when in a speech to Parliament James I said he ‘detested’ the Catholic faith. Days later, he ordered all Jesuit and Catholic priests to leave the realm. Following the king’s declaration, Catesby joined forces with other Catholic conspirators to bring down the Protestant government.”

The changing history of Bonfire Night is a fascinating one, as it moved from official Church-led commemoration to anarchic celebrations and episodes of public disorder during the 18th century to a more regulated holiday during the Victorian period. It would would come be called Guy Fawkes Day (after the conspirator found guarding the gunpowder hidden beneath the Houses of Parliament) during the Victorian period. Local bonfire societies organized celebrations that culminated in burning a Guy Fawkes effigy. By the early 19th century, the tradition of children collecting money to buy fireworks for the celebration - with their homemade effigies and chants of “Penny for the Guy” - had taken hold. Gradually, the night became as much, if not more, about the fireworks display than the original story upon which the entire holiday was based. But it clings on here and there, and only yesterday in Brighton’s North Laine, I came across a couple of boys collecting pennies for the Guy.