Love of place is so contingent on other life passages. This contingency, and the not-said of personal history mark anything I say here. At any rate, some confusion and rootlessness aside, it’s a lucky problem to have. I thank my father for putting a passport in my hands at an early age.

Chance and a few life choices would have it that I’ve lived more years in Britain than anywhere else, including my U.S. homeland, yet I’ve always said that British culture was the more elusive, difficult, opaque one. Britain is a kind of ‘third home’, bearing in mind that this says nothing about the longevity or importance of a place to a life story. It’s only that the U.S. provided the origins and childhood, whereas France, where I spent five years in my twenties, had an immediate and enduring hold on me. I fell in love fast and never fell out of love. I had a sense of grasping meanings there. And the meanings were all about difference. In language and expression, I found a different self there, one that I liked. I still like her. When I return to France each year, it is as though the other self is there waiting for me. Coucou Ameee! Interestingly, I rarely write about France. It is as though there is no need. France is a place to be, a freedom from writing. The U.S. means to be ever digging for origins and lost promises. Britain is a prolonged estrangement turning, very gradually, into a negotiated relationship.

The estrangement has never been a bad thing. Just interesting. It’s been the making of my adult years, for better or worse. First, it altered my relationship with America in a specific way. It made me love my birthplace like a lost treasure, mythologize it, and sometimes view it as though the whole thing were a film. From Buster Keaton, the Marx Brothers, and Frank Capra to David Lynch, the Coens, Terrence Malick, Kelly Reichardt, Jim Jarmusch, and more. Yet when the house lights come up, I know I am conflicted about my homeland. I have grown an ‘outsider’s eye’ and attached it to an insider’s past. And the more ‘past’ my past becomes, the more bewildering America seems.

Perhaps this growing bewilderment has finally helped bring about a recasting of things here on English ground. I can’t help but notice that some subtle shift has occurred - say over the past decade. A realization that, despite my frequent declarations about how utterly incomprehensible England is, some deeper knowledge was forming. Not the knowledge of one born here. Not the deep-set awareness of regions and accents, class slights, post-imperial cruelties, and historical divides. Not the grasp of those stereotypical, grain-of-truth traits we talk about – British reserve, eccentricity, concealed meanings. I have a sense of these, even a competence in many of them, but they remain foreign in my mind.

But yes, knowledge comes, even if it hides beneath everyday consciousness. And more than that, affection comes. I am now regularly struck by waves of love for the UK. As with America, it is not uncritical, but it is surprisingly committed. It’s a love of landscapes and people. Early friends here and recent ones too. Footpaths in Yorkshire, Devon, and Scotland. Walking across moorlands to a country pub. Particular London bus routes and tube lines. The National Health Service, postwar Britain’s greatest achievement. The BBC, for all its flaws. Labour Party meetings that got out of hand. Pub gatherings after Labour Party meetings that got out of hand.

Soldered to these general affections are tiny incidents and rites that burn brightly in my memory. Past moments of small cultural learning. The police officers who came to our London flat after it had been burgled to tell us they had little hope of catching the robbers, and we’d best just make a cup of tea and an insurance claim. Yes, many cups of tea are still brewed to punctuate arrivals, meetings, and minor crises - the sentences and paragraphs of British time. Thank goodness coffee has made such inroads here. Last orders in the pub. The old men in a Lavender Hill pub way back in 1976 who talked me into singing Maybe It’s Because I’m a Londoner with them. A friend who, not trusting himself to heed the BBC announcement, “Look away now if you don’t want to know the results,” put a blanket over his television set on Saturday evenings so that he could enjoy ‘not knowing’ until Match of the Day came on after the nighttime news. The London Underground ticket seller at a far East London station who, upon my purchase of a ticket for Willesden Green in northwest London, quipped that he’d once been “over there” on holiday. Visiting my friend, Rachel, when she lived in Brixton. I rose early to pop to her local newsagent, and before I could speak, the young fellow behind the counter sized me up immediately. “Guardian?” he said. And we both laughed. There are dozens of these moments if only I would stop to chronicle them.

Most often, it’s the month of November that prompts these wider memories and affections. They seem to begin with cold and damp November evenings in 1979 that spill into the November of 1980.

The time is out of joint. I dream myself back. I dream myself young and green.

Willesden Green: 1979-80

Everything here, however old to the surrounding culture, is new to me. London, once called the Monster City, is uncontained in its scale and perplexity. Had I studied History by now, I might say that England – to this young American – is like stepping into the long post-war. But that’s not it. Thatcherism has come. The misted black-and-whiteness of the place possesses something – we don’t yet know what – to do with Thatcher’s vision of Britain. It is the turning from the postwar period to something that would prove harsh as if by electoral choice, cruel in its unique way.

Willesden Green is mostly terraced houses divided into flats and bedsits.[1] We have what we need: a corner shop, a greengrocer, two or three pubs and breakfast cafés, and the tube station. I work as a sales assistant in a print shop off Fleet Street. I travel by tube every day, returning home to Willesden Green Station. Anyone can fall in love with London Underground. I do.

The flat is a refrigerator. Colder and darker than the outside. I teach myself to operate without central heating. The first task upon returning home from work is to make a coal fire. Don’t wait. Don’t take off your coat under the mistaken impression that you’ll be able to face it later. You won’t. Make the fire now. Other things can wait: food, drink, life, thinking. You start with firelighters, kindling if you have it, rolled-up newspapers. Put your match to them. Add coal strategically. Don’t rush this step or you risk going back to cold-jail immediately. Before the firelighters and kindling have gone out, spread open a page of yesterday’s Guardian and hold it over the chimney opening to encourage the small fire you are birthing. Behind the page which you find yourself reading again, the fire sucks and pops and leaps. You’re waiting for the flames to grab the coals irreversibly. When the paper begins to scald, press it into a ball and add it to the fire, making sure it doesn’t fly up the chimney. A skilled fire builder may only need one sheet of newspaper. I am not skilled.

An hour later, I am eating a tinned steak and kidney pie (made by Fray-Bentos since 1881, the label claims) and drinking a glass of cheap red wine that I have warmed in a saucepan on the gas cooker. Soon, my flatmate will come home. He’s a philosopher and classical pianist. We talk about music, sexuality, and Spinoza. I can’t know it yet, but he will remain a dear friend in the years to come.

There is a box television next to the fire. I watch the news and Top of the Pops. By January 1980, The Specials are on: Too Much Too Young. I don’t know it yet, but the band will remain in my mind. The band marks this moment. Willesden Green. The flat like an icebox. Making fires night after night. Early jobs in London. Riding tube trains. Getting lost in the city. Music and the resistance to Thatcherism.

My Willesden Green year that starts with The Specials ends with them rocking their Christmas jumpers while singing about a “life without meaning” and “trying to find a future” again on Top of the Pops with Do Nothing. The Specials’ Ghost Town was a year away, but coming.

In 1981, I move from Willesden Green to Finsbury Park. The Rainbow Theatre, best of the old gig palaces, is only down the road. One day, I will lose count of the bands I see there, most of them with a close friend. In May 1981, we see The Specials. By the end of the year, the great concert period at The Rainbow will be over. The last gig, on Christmas Eve, is Elvis Costello and the Attractions.

I can’t know it, but in 2022, all those years later, I will experience a terrible longing to pick up the phone and say to my friend, “Terry Hall has died. Do you remember when we saw The Specials at the Rainbow?” But she won’t remember, and this might confuse and upset her because she is losing her memory. Very fast now. I won’t pick up the phone on that distant, unimaginable day in 2022.

Penny For the Guy: Finsbury Park

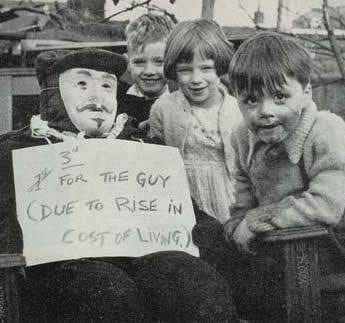

Not long after the move to Finsbury Park, I am exiting the tube station when I hear the kids calling, “Penny for the Guy.” They look something like this group:

I know, at the time, very little about the Gunpowder Plot.[2] I don’t foresee the coming decline in Bonfire night celebrations, although there are places – Lewes, for example – that will continue to hold large events, burning effigies of Putin, Trump, and other tyrannical figures. In the coming decades, fireworks will yet be heard pounding and crackling from small local celebrations, but Halloween will jostle for position as the autumn holiday.

The kids on corners asking for pennies will be lost in time. I don’t know it yet, but this is the passing encounter that will remain strongest in my recollections of London, and seem most ‘English’ - a memory of kids, underdressed, feeling the cold, but joyously free for a few hours. Little rebels on London street corners and in the entrances to tube stations.

[1] Willesden Green, the Kinks song (1971) has been and gone. I won’t discover it until decades later by which time it won’t seem very Kinks-like.

[2] See, for example, What is the story behin Bonfire Night? Royal Museums Greenwich: “The Gunpowder Plot was a failed attempt to assassinate King James I of England during the Opening of Parliament in November 1605. The plan was organised by Robert Catesby, a devout English Catholic who hoped to kill the Protestant King James and establish Catholic rule in England… English Catholics had expected more religious tolerance under James I compared to the reign of his predecessor, Elizabeth I. However, these hopes were dashed in early 1604 when in a speech to Parliament James I said he ‘detested’ the Catholic faith. Days later, he ordered all Jesuit and Catholic priests to leave the realm. Following the king's declaration, Catesby joined forces with other Catholic conspirators to bring down the Protestant government.”

absolutely love this piece - the fire-lighting passage with pages of Guardian getting crisp. I'd like to say - long live this process and the satisfaction of masterful technique. Long-live the open fire in Victorian Terrace houses. But no longer on sustainable ground.

Love this Amy. Your remembering takes me back to the pictures in my own head. You write so beautifully about moments in time.