We are haunted by photographs in our possession, old photographs that from time to time we regard, hold in bare hands, touch with our fingertips, brush with our “cracked country lips.”1 The same photographs that at other times, our eyes cannot bear to see. Our eyes fear tidal waves. To grasp and see the photo and yet go on living seems, well, a kind of betrayal. To preserve ourselves and let the lost ones sleep in untroubled death or live apart, we put the photograph away.2 Somewhere safe. For those other times.

I am looking at my mother and her mother before they died and after they died. I see a land of before from the land of after. I see my face in my mother’s face. She looks back at me, catching sight of how her girlish face will age. Our eyes meet for an instant. Then she is gone, though I hold the moldering print in my hands.

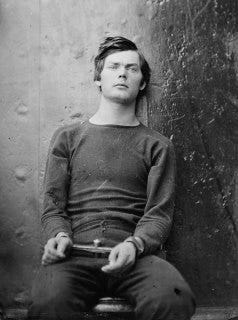

To take a public though disturbing parallel, Barthes turns to Alexander Gardiner’s portrait of Lewis Payne as he waits to be hanged (Payne was one of the Lincoln assassination plotters). Barthes notes that the “flash” he experiences in looking at this photograph is not so much its historical interest, but the realization that the condemned man is going to die. Yet (as Barthes comes to the photograph a century later), Payne is already dead. This is what Barthes reads in the photograph. “He is dead and he is going to die… This will be and this has been… giving me the absolute past of the pose, the photograph tells me death in the future.” (Camera Lucida)

For Barthes, this is revelatory of something poignant in his responses to his private photographs. He moves from Lewis Payne to a particular photo of his mother:

“What pricks me is the discovery of this equivalence: in front of the photograph of my [now dead] mother as a child, I tell myself: she is going to die. I shudder… over a catastrophe which has already occurred.” (Camera Lucida)

We already know that “as soon as the shutter clicks, what was photographed no longer exists.” (Marjorie Perloff, “What Has Occurred Only Once,” 1997). But now Barthes brings death and history to the center of the frame. He reminds us that the same period saw the inventions of photography and History (as a field of study). Jules Michelet conceived of History as “love’s protest” against historical loss. This is grand scale stuff, but as Barthes notes, it can be pulled back to our smallness:

“In front of the only photograph I find of my father and mother together, this couple who I know loved each other, I realize: it is love-as-treasure which is going to disappear forever; for once I am gone, no one will be able to testify to this.” (Camera Lucida)

Yes, love’s protest against our losses. This, in part, is why our photographs of loved ones bring anguish, even as they may bring a smile of recognition, and memories we wish to preserve despite the impossibility of memory remaining intact. Each of us knows which of our cherished photographs in our collection produce this dual effect. There are times when we need to look and times when we cannot bear to look.

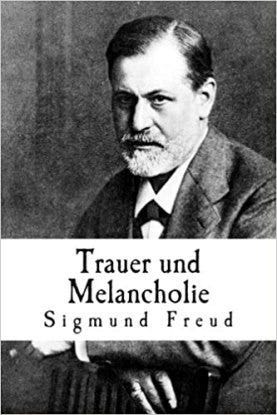

Perhaps it is through this contradiction that photographs may come to our aid during the “work of mourning” following a death, the process described so eloquently by Freud in his 1918 essay, Mourning and Melancholia. In a discussion of photography relating to Freud’s seminal essay, Christian Metz reminds us that mourning is, after all, “an attempt to survive.”

We learn to love the person “as dead, instead of ignoring the verdict of reality, hence prolonging the intensity of suffering.” (Metz, “Photography and Fetish,” 1985)

The funeral rites that exist in all societies have a double signification: “a remembering of the dead, but a remembering as well that they are dead, and that life continues for others.” (Metz, 1985)

“Photography, much better than film, fits into this complex operation, since it suppresses from its own appearance the primary marks of ‘livingness,’ and nevertheless conserves the convincing print of the [deceased person]: a past presence.” (Metz, 1985)

“All this does not concern only the photographs of loved ones… There are obviously many other kinds of photographs: landscapes and so forth… In all photographs, we have this same act of cutting off a piece of space and time, of keeping it unchanged while the world around continues to change, of making a compromise between conservation and death.” (Metz, 1985)

Writing in the pre-digital age, Barthes noted the decay of the photographic print:

“Like a living organism, it is born on the level of the sprouting silver grains, it flourishes a moment, then ages… Attacked by light, by humidity, it fades, weakens, vanishes; there is nothing left to do but throw it away.”

“Earlier societies managed so that memory, the substitute for life, was eternal and that at least the thing which spoke Death itself should be immortal: this was the Monument.” (Barthes, Camera Lucida)

On a moor in West Yorkshire, my friends made a cairn and have been adding to it since their Border Collie died some years ago. When my Labrador, Agnes, died just before the pandemic, my friends took me up to the cairn so that I might add a stone for her. Ever since, they have kindly sent me regular photographs of the cairn, adding to it on each of their walks up that way. Sometimes Jessie, their new Collie, appears alongside the cairn in the photographs. Life beside death.

When I cannot bear to look at photographs of Agnes, or Gladys (now, more painfully, lost to me in life), I look at this photograph of the cairn instead, a photograph of a monument to lost dogs.

Barthes may lament the passing of the monument in the age of the photograph, but it is Barthes who grasps what, from its very beginnings, made photography so powerful: its character of invisibility. In other words, I see the cairn, the monument, not the photograph. The power of the photograph’s content overcomes the photograph as object.

Show your family photographs to someone. She may show you hers. She won’t say, “Look, this is a photograph.” She is more likely to say, for example, “Look, this is me as a child. Here I am with my parents in the old house. Here’s my brother with his best friend. Here is my dog who died or went away. Here is the cairn.” And so forth.

We’ve all had these exchanges. Memories we try, mostly in vain, to share with others. Our desire for proof of lives lived, proof of a past, evidence to which we cling. Beings gone from our lives through death or because we have let them go. The photograph, Barthes reminds us, is rarely anything but a recitation of “Look, See, Here it is.” Or more aptly, here it was.

Here she was. My mother. She is gone. I will be gone, but I am here today. When it’s too hard to look at her, I may choose to look at the distant cairn instead. Yes, it’s just another photograph, and the work of mourning, once started, is unending. But it is good work.

With thanks to Bob Dylan. “Your cracked country lips, I still wish to kiss as to be by the strength of your skin.” (To Ramona, 1964)

“We might think of sleep as the benign, nourishing, restorative version of giving up; as a rather more reassuring, indeed enlivening, picture of what it might be to give up… Every night we give up: give up consciousness, give up thinking, give up vigilance, give up alertness, or inertia, give up, and give up on, waking life.” (Adam Phillips, On Giving Up, 2024)

Beautiful, Amy!