The Threshold God (two)

Houses, history, and dreams of staying/leaving (written during Covid times)

“No dreamer ever remains indifferent for long to a picture of a house.”

(Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, 1958)

The dates on Kodachrome slides. I recall how Christmas came to stamp a moment. During the holidays that year, my parents began to talk about moving. Not far. One suburb to another, a short distance in miles. I didn’t take them seriously until they began visiting model houses across the town line. Then I began to worry.

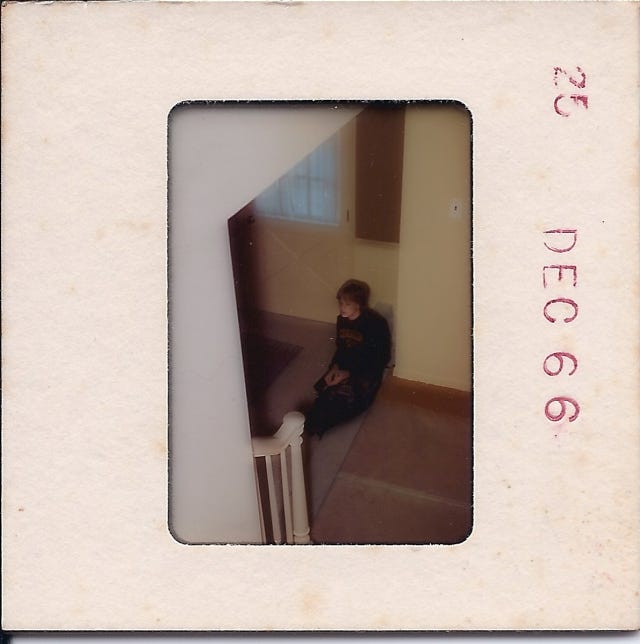

My father took the picture in a model home. I was twelve years old. My parents were viewing the house and I waited for them at the foot of the stairs. The worrying had set in.

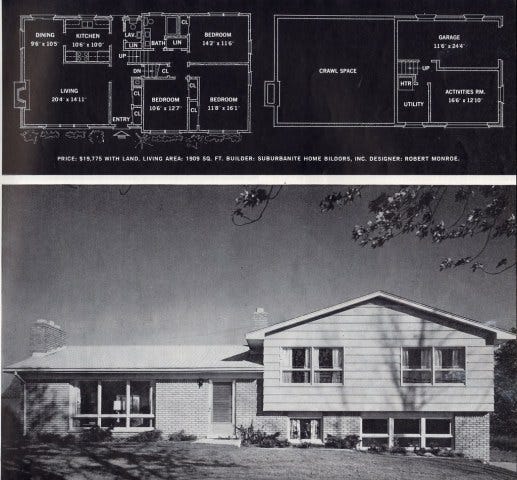

In spite of the disquietude, unspoken to my mother or father, I liked the split-level design that looked something like this:

The upward mobility of suburbia. Concentric rings, a series of retreats from the city. If you drove outward crossing the imaginary line of each ring, you mapped increasing affluence. You left behind our brick bungalow, a little box house, yet also once a model home:

Packaged houses and packaged suburbs had been proliferating around Detroit since before the fifties. Cheap mortgages on the GI Bill escalated it all. Property developers, the Henry Fords of suburbia, borrowed assembly line tactics for their trade.

I once overheard my father say that he disliked old houses. He said he could only move to a new house, one with no prior inhabitants. He was a son of the Depression who went to war. Was this too, part of the success of the postwar subdivisions? A haunted generation in search of newness and forgetting?

The new suburbs were called vetsvilles (for the soldiers), bedroom towns (for the GIs who had become commuting husbands), wombs with a view (for the baby boom years). The new suburbs were white, but nobody mentioned this at the time. Nobody mentioned the persistent housing discrimination, redlining, blockbusting, or other practices that made our northern spaces segregated. These were the fault lines beneath the foundations of our little houses and the newly grassed yards. The fault lines ran beneath our feet and disturbed our dreams.

We had moved to the little brick bungalow in 1956. I was two years old.

I don’t know when I began to notice the internal discord, the dissonance in my thoughts, a recurring dream. I was too young to name the subtle changes. There might have been a moment – an incident or glimpse of something – but I can’t locate it. I only know that from an early age, I loved our house and street, loved them intensely. But I grew suspicious of them.

It was an uncomfortable sense which manifested itself in seemingly unrelated and inarticulate childhood fears. But at its core was a slow realization that I wanted never to leave and I wanted always to leave.

It was a psychic disturbance, but it arrived from outside. It came from the corners of our house, patches of dandelions on our lawns, front porches, cracks in the sidewalks, end of the street, edge of the town with its through roads that led to Detroit in one direction, and distant farmlands in the other. It came from these external spaces, but it burrowed inside. The disturbance never left me. It shaped nearly every decision, especially every departure that I would make in the years to come.

My parents didn’t purchase the split-level model where my father took the Kodachrome slide of me at the foot of the stairs. There was a reprieve after that Christmas. But the following year, they bought a wooded acre lot far from Detroit, a set of plans for a Cape Cod-style house, and they hired a builder. I would never love the Cape Cod. I don’t love it now. I can’t even locate a photograph of it.

But it was the upgrade to the Cape Cod that would make the other place, a bland box house on a street of fifteen or so other houses of the same design, the site of my dreams.

You will say it is only because I was a child there. Because I wish to relive my past. It’s not so much to do with the little house on the edge of Detroit.

To which I reply, No! Where is the difference between me, my past, and this place?

“Indeed, as I see it now, the way it appeared to my child’s eye, it is not a building, but is quite dissolved and distributed inside me: here one room, there another, and here is a bit of corridor which, however, does not connect the two rooms, but is conserved in me in fragmentary form. Thus the whole thing is scattered about inside me…”

(Rilke, The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge, 1910)

Here, Rilke comes close to Bachelard’s insight that our bodies carry our important spaces. Our bodies remember. Our dreams remember.

“… the house we were born in is physically inscribed in us. It is a group of organic habits. After twenty years, in spite of all the other anonymous stairways, we would recapture the reflexes of the ‘first stairway,’ we would not stumble on that rather high step… We would push the door that creaks with the same gesture, we would find our way in the dark to the distant attic. The feel of the tiniest latch has remained in our hands.”

If, after Freud, we seek to know ourselves through our dreams, daydreams, and memories, then Bachelard spatializes that project:

“A psychoanalyst should, therefore, turn his attention to this simple localization of our memories. I should like to give the name of topoanalysis to this auxiliary of psychoanalysis. Topoanalysis, then, would be the systematic psychological study of the sites of our intimate lives.”

Therefore, what I am must make reference to the brick bungalow. The brick bungalow is of topoanalytic significance. And to take again from Freud/Bachelard, the brick bungalow is my oneiric (related to dreams/dreaming) house. And once we leave childhood behind, we may be haunted by the house:

“…there exists for each of us an oneiric house, a house of dream-memory, that is lost in the shadow of a beyond of the real past… But the houses that were lost forever continue to live on in us; they insist in us in order to live again, as though they expected us to give them a supplement of living. How much better we should live in the old house today!” (Bachelard)

Pressed into our spaces today, we dream of our pasts. The old spaces return. How many people have told me that their dreams, since the lockdown, have become more vivid and frequent?

In dreams, and now in waking hours, we watch our doors and wait.

“If one were to give an account of all the doors one has closed and opened, of all the doors one would like to re-open, one would have to tell the story of one’s entire life.”

“Why not sense that, incarnated in the door, there is a little threshold god?” (Bachelard)