It would be easy to repeat Joan Didion’s evocative and much-quoted statement, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.”[1] And much as I too appreciate the line, the ring of it, the emotive force of it, I realize it cannot serve my purposes here. So, I wish to vary it a little to the following: We tell ourselves stories in order to remember. We tell ourselves stories because we forget. We tell stories to fight the failures of memory. And when we fail to overcome failure, we tell more stories so that we might at least believe we remember.

Not long ago, I spent a week with a dear friend who is living with a severe memory disorder. As we walked around the town where I now live, she regularly told me she remembered this place or that, often adding a small account of some gathering or event at that location. It is unlikely, though not impossible, that she visited these locations years ago. I believe the events she recounted took place in some form and some (other) place. But the important point is that it made her feel better to tell me them, to insert herself into time and place, and be seen as my equal in the game of memory we all play with varying accuracy and competence.

We are all vulnerable in that lifelong game of memory, and few rounds are more telling of that predicament than the ‘earliest memory’ round. “What is my earliest memory?” we like to ask ourselves.

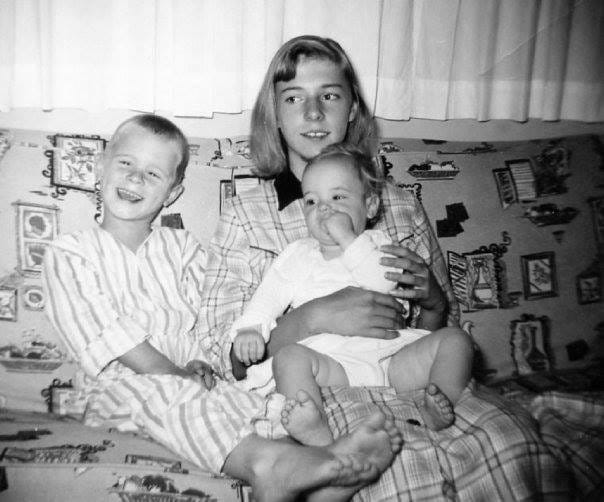

This is a photo of me as a baby, together with my elder sister and brother. Of course, I don’t remember the moment of the photograph or any particular event relating to it, but I remember the sofa. More than that, I have come to fix upon the sofa as an “earliest memory.” It is as though its pattern and texture left an imprint on my infant mind, settled somewhere behind my eyes, and deposited traces on my fingertips so that I might always recall the images and stiff cottony ‘feel’ of that 1950s sofa.

But something is wrong. There is a nagging doubt, a sensation of unreliability. This has to do with an amnesia written into our human condition from the start. There are two matters to pursue here.

First, the old sofa comes to me as a sense memory, one invoking the two specific senses of touch and sight. As such, it has no explicit grammar, no words, or narrative other than what I might impose upon it retrospectively. In this, it resembles a dream. Freud remarked that “words are often treated in dreams as things.”[2] Dreams turn our latent thoughts/wishes into images or scenes (the dream’s manifest content) which we, upon waking, try to put back into words. We seek to recover a meaning that the dream has disguised.

Yet for this particular memory, this waking dream, I struggle to find a way back from sense memory to words or meaning. All I have is a remote, untethered flash of recognition accompanied by affect – in this case, a pang of bittersweet longing (nostalgia) brought on by the familiar sight of the sofa.[3] Again, we find a parallel in Freud’s conception of dreams. He cites Austrian pathologist Salomon Stricker’s remark: “If I am afraid of robbers in my dreams, the robbers, to be sure, are imaginary, but the fear of them is real.” To which he adds,

“…the same thing is true if I rejoice in my dream. According to the testimony of our feelings, an affect experienced in a dream is in no way inferior to one of like intensity experienced in waking life, and the dream presses its claim to be accepted as part of our real psychic experiences, by virtue of its affective rather than its ideational content.”[4]

I can perhaps stake some claim to the sofa as a sensual and ‘dreamlike’ early memory, even if I derive no description of a past self or event from it. Even if I find nothing more than the immediate affect it rouses, even if I experience no Proustian passage from involuntary to autobiographical memory because, and here I borrow more playfully from Mr. Freud, “the affect is always in the right.”[5]

But – and here is the second matter of note about this memory – my certainty that the sofa, as sense memory, might be claimed as earliest memory – is as fleeting as the memory itself. Is it a telltale sign that my memory of the sofa is in black and white? When I think about the sofa, I cannot ‘see’ its colors, though I retain an impression of its pattern and feel. The photograph as material object is, perhaps, vying with its image content (the old sofa) for power over me. As tightly as I might cling to my memory of the sofa, my more cautious self must admit that it did not occur to me as a ‘first memory’ until I found the photograph. My discovery of the photograph happened in 2003, after my mother died, in the course of going through her belongings.

Did the discovery of the photo trigger a ‘real’ first memory or did it simply encourage me to create a narrative? Something along these lines: I have a first memory and here it is. Finally! I have found my first memory. In other words, the photograph helped me to tell myself a story of remembering. A story more about memory itself than about the sofa. We tell ourselves stories to remember. To find the “affect that is always in the right.” Here, Freud might also draw my attention away from my ‘dreamlike’ descent into nostalgia to remind me of what he called “infantile amnesia… that failure of memory for the first years of our lives,”[6] that “turns everyone’s childhood into something like a prehistoric epoch.”[7]

So, we arrive at this pathos, this realization that any effort to identify first memories must reckon with forgetting. If life were a room, then remembering and forgetting would jostle for space inside its door. Those of us who are growing older know that forgetting may gain the upper hand before we make our exit. But we can note that this is nothing new. It has happened before, in our earliest years.

The experience of infantile amnesia has been much researched and reworked since Freud, and childhood amnesia is now viewed as a cognitive phenomenon best understood as having to do with child brain development, specifically the brain’s capacity to encode memories. What we now know is that childhood amnesia emerges around the age of seven. Up to then, children are remarkably good at remembering earlier events:

“Although adults exhibit limited abilities to retrieve memories from their early childhood, young children, including toddlers, are capable of recalling information about their past experiences following delays of days, months, and even years. Yet many of the early memories become inaccessible or “forgotten” as children grow older such that by late adolescence, children exhibit childhood amnesia to a similar extent or magnitude as adults do.[8]

There is now broad agreement that the emergence of childhood amnesia can be explained by brain development. Although two-year-olds can answer basic questions about recent events, they tend to need prompting or cue words to do so. For the next few years and as they acquire language, they grow more proficient at recalling and describing life events. Yet as this skill progresses – i.e. as they learn to narrate their past, to develop a sense of autobiographical memory – that progress coincides (from about the age of seven) with a forgetting of those early events that occurred before the brain began to achieve that narrative capability. This is why most researchers agree that our earliest memories usually date from age three or four.

Here we have one of life’s bittersweet ironies, almost another recasting of Didion’s statement insofar as our developmental ability to narrate our pasts (tell ourselves stories about our pasts) coincides with the loss of three or four years of memory. Indeed, psychologist Romeo Vitelli notes that “Since narrative retelling allows us to ‘rehearse’ important memories and retain them longer, memories that are not rehearsed become inaccessible over time and can be quickly forgotten as a result.”[9]

Vitelli cites further research showing that the rate of forgetting is most accelerated during the period in which childhood amnesia emerges, i.e. around the age of seven, when…

“children rapidly forgot memories of early childhood, but that forgetting slows as children grow older. This suggests that the number of available memories relating to early childhood rapidly shrinks in children. For adults, however, memory is less vulnerable to forgetting due to better memory consolidation.”[10]

Memory consolidation refers to the gradual development and rehearsal of autobiographical memory, the ability to narrate our past and repeat those narrations over the years. And here, it’s important to recall that we constantly revise our memories. No one has made this point more eloquently than Freud:

“It may indeed be questioned whether we have any memories at all from our childhood: memories relating to our childhood may be all that we possess. Our childhood memories show us our earliest years not as they were but as they appeared at the later periods when the memories were aroused. In these periods of arousal, the childhood memories did not, as people are accustomed to say, emerge; they were formed at that time. And a number of motives, with no concern for historical accuracy, had a part in forming them, as well as in the selection of the memories themselves.”[11]

The reader will forgive me for returning to this passage often, but it is our best reminder that memory is a form of representation as much as it is a cognitive process. This passage, we might say, is where Didion and all auto-biographers/memoirists/artists before and after her come to meet the psychologists and neuroscientists. As beings who remember and forget and remember and forget with varying degrees of accuracy (cognition), we all must have recourse to the narrative devices of storytelling (representation).

Moreover, all storytellers benefit from cues, props, and stories told by others. So, what happens to our seven-plus-aged selves as we start to develop autobiographical memory? We begin to gather and create our archives. We gain photographs, mementos, household objects, family heirlooms, and a host of other personal and family possessions. My father clung to his high school basketball trophy, won only a year before he went to war, for his entire life and I now keep it in my possession; I held onto my first ice skates until a transatlantic move pressed me to give them up.

And of course, we absorb the narratives of others, initially our parents, then as our world widens, extended family, friends, and colleagues. Here, it is worth noting that those early (and even later) childhood memories we believe we remember often derive from memories handed to us by our parents or other close family members. For example, I have a deep fear of swimming too far out (losing my footing) in any lake, ocean, or pool. I am certain this fear comes from a memory of a near-drowning incident that occurred when I was four or five. But rather like the nostalgia I experience upon seeing the old sofa, the only real memory (or perhaps more accurately, a triggered return) is of an affect - in this instance, fear of deep water.

I possess no memory of the incident itself, but I regularly catch myself believing that I do. This is because the near-drowning incident entered the family annals to become an agreed story, an explanation even, of a child who exhibited terror at the thought of swimming in a lake. Soon, this ‘memory’ was little more than what various people said happened. It was revised as it passed from one person to another, one year to another. Sometimes, I was told it happened when I was four. Sometimes, I was five. Sometimes they said, “Now what year was that?” The event, unlike my fear, receded.[12] To borrow from Freud again, the affect (fear) had the last word. The affect that is “always in the right”, however degraded the memory itself.

I began this piece by describing a recent visit from a friend who has a disorder of memory. She grapples, from minute to minute now, with the decay of her memory. There is something in this universal story of childhood amnesia that levels us. Brings the two of us closer and provides a tiny window of shared experience. I know she’ll soon forget our week together if she has not done so already. I, with all the failings and fictions of human memory all too evident to me, will remember for both of us as long as I can. But we will forget together before it’s all over. That too is a story of our friendship.

[1] Didion, Joan. 2009. The White Album. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 11.

[2] Sigmund Freud. 1900. The Interpretation of Dreams, 1900. In Sigmund Freud, and A A Brill. 1938. The Basic Writings of Sigmund Freud; Tr. And Ed., with an Introduction. New York, Modern Library, 330.

[3] I use the word affect, here, to refer to the “experience of feeling or emotion, ranging from suffering to elation, from the simplest to the most complex sensations of feeling, and from the most normal to the most pathological emotional reactions. Often described in terms of positive affect or negative affect, both mood and emotion are considered affective states.” See the Dictionary of Psychology, American Psychological Association.

[4] Sigmund Freud. 1900. The Interpretation of Dreams, 1900. In Sigmund Freud, and A A Brill. 1938. The Basic Writings of Sigmund Freud; Tr. And Ed., with an Introduction. New York, Modern Library, 434.

[5] Ibid. 435. See also, “The Proust Phenomenon,” The Memory Network: “The ‘Madeleine’ episode, the starting point of Proust’s seven-volume novel of memory and of time, has been understood since its appearance as a major innovation not only in the field of modernist literature but in our understanding of the mind, and of the way in which the workings of the human sensory system can affect our knowledge of ourselves and our own past. The incongruous force of a moment of perfect recall granted by a cake dipped in tea, and of the power of the senses to erase distances across time and space without prompting, gave rise to the concept of the ‘involuntary memory’, and to an accompanying sense of pathos summed up in the novel’s title.”

[6] Freud, Sigmund. 1901. “Childhood and Concealing Memories” in Psychopathology of Everyday Life. In Freud, Sigmund and Brill, A.A. 1938. The Basic Writings of Sigmund Freud; Tr. And Ed., with an Introduction. New York, Modern Library, 64.

[7] Freud, Sigmund. Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality. In Freud, Sigmund, and Gay, Peter. 1995. The Freud Reader. London: Vintage, 260.

[8] Wang, Qi and Sami Gülgöz. 2019. “New Perspectives on Childhood Memory: Introduction to the Special Issue.” Memory 27 (1): 1–5, 2.

[9] Vitelli, Romeo. 2014. “Exploring Childhood Amnesia,” Psychology Today. Online post: Exploring Childhood Amnesia | Psychology Today United Kingdom

[10] Ibid.

[11] Freud, Sigmund. Screen Memories, 1899. In Freud, Sigmund, and Peter Gay. 1995. The Freud Reader. London: Vintage, 126.

[12] For a short story based upon this incident and with an invented ‘future’ for its related fear-of-drowning, see Sugarbush Lake.