“The lover of photography is fascinated both by the instant and by the past. The moment captured in the image is of near-zero duration and located in an ever-receding ‘then’. At the same time, the spectator’s ‘now’, the moment of looking at the image, has no fixed duration. It can be extended as long as fascination lasts and endlessly repeated as long as curiosity returns.” (Peter Wollen, “Fire and Ice” in The Photography Reader, Liz Wells ed. 2003)

This is the story of one photograph. A story that began before the digital era.

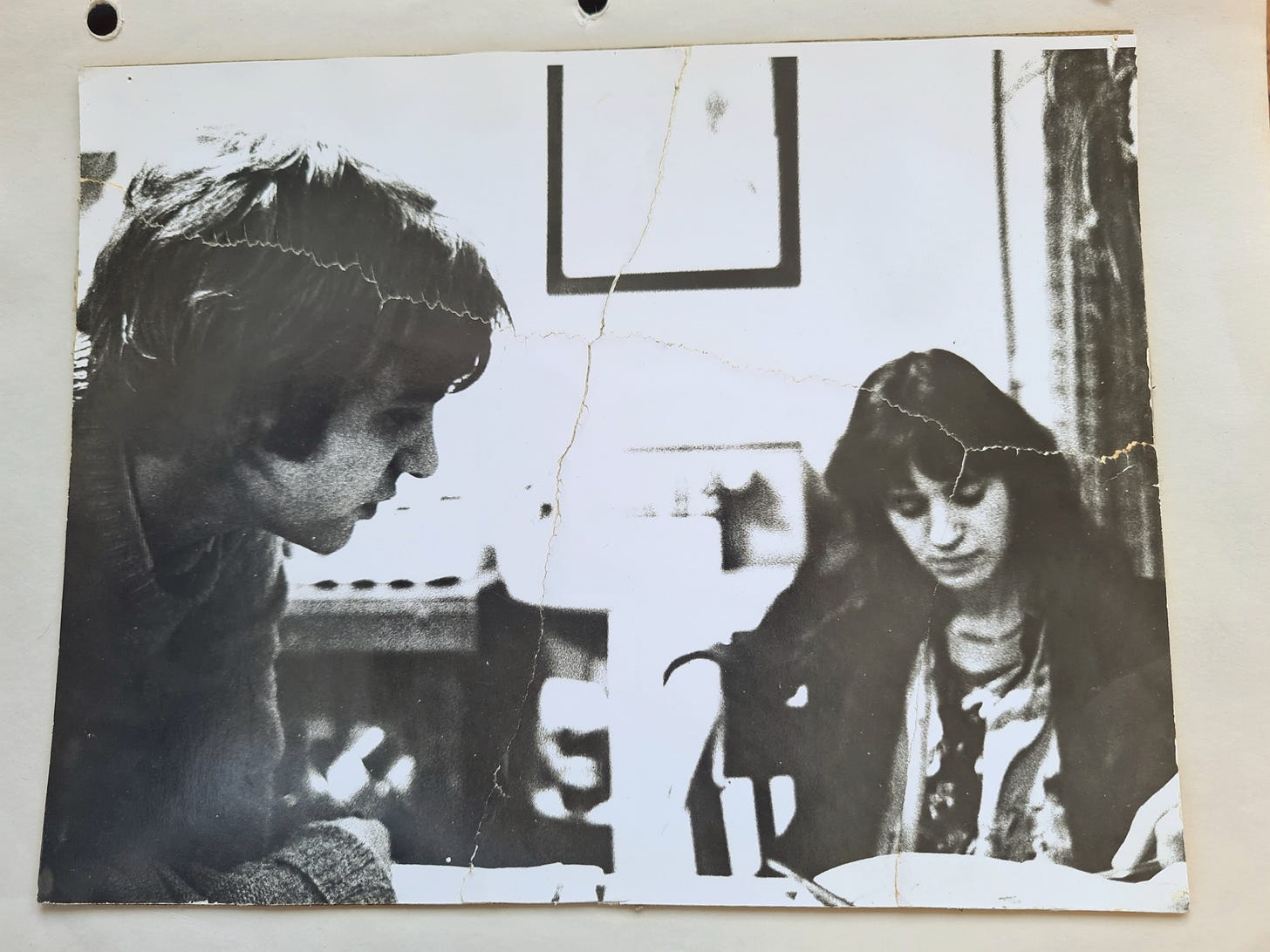

Here is a picture of Ricardo and me, taken in 1978. We are in the kitchen at Crescent Street in Northampton, Massachusetts. Some of you may remember this kitchen. It’s where I first met Bob Rhodes. He was sitting where I am sitting in the photograph.

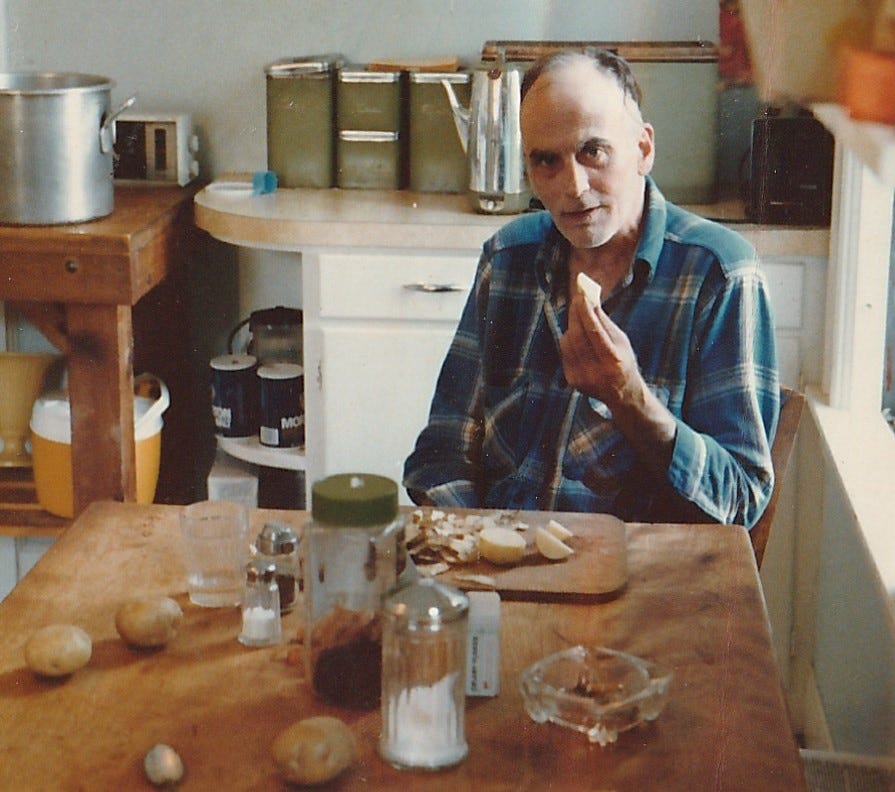

Here he is again, for those who don’t remember. He is chopping potatoes and talking to them. The little potato pieces are begging him (Bob does the voices) not to put them in the oven. (For the story of Bob, his potatoes, and much more, see Postcard #1)

It was a very basic little kitchen, in need of updating. But I loved it because these two photos were taken there and because it was Crescent Street, where Ricardo and I lived and worked as mental health support workers. I took the picture of Bob. But who took the one of Ricardo and me? Normally, I was the photographer, but I am in the picture. It could have been Michael, our dear friend and colleague. It could have been one of the Crescent Street residents. Bob or one of the others. They were nearly all, at various points, interested in the camera. Ricardo thinks it may have been Cathy who was regularly at the house and always carried her camera. (See Postcard #15, Cathy) She and I both had darkrooms, but the print paper seems more like Cathy’s than the one I was using at the time.

When I study the photo, I wonder what we were talking about that day. We look young and serious. I notice Ricardo’s profile and the tilt of his head, so familiar. His sleeve. He wore what he always called his ‘fisherman’s jumper’. I remember Bob and feel sad. My photographer’s eye sees how poorly lit the scene was. The kitchen was at the back of the house and often dark. Whether Cathy or I printed it, there was little to be done about the severe contrast, extreme blacks and whites with a loss of detail, and the intense graininess of the greys. It would not have been a quality negative to begin with, and very hard to correct its flaws.

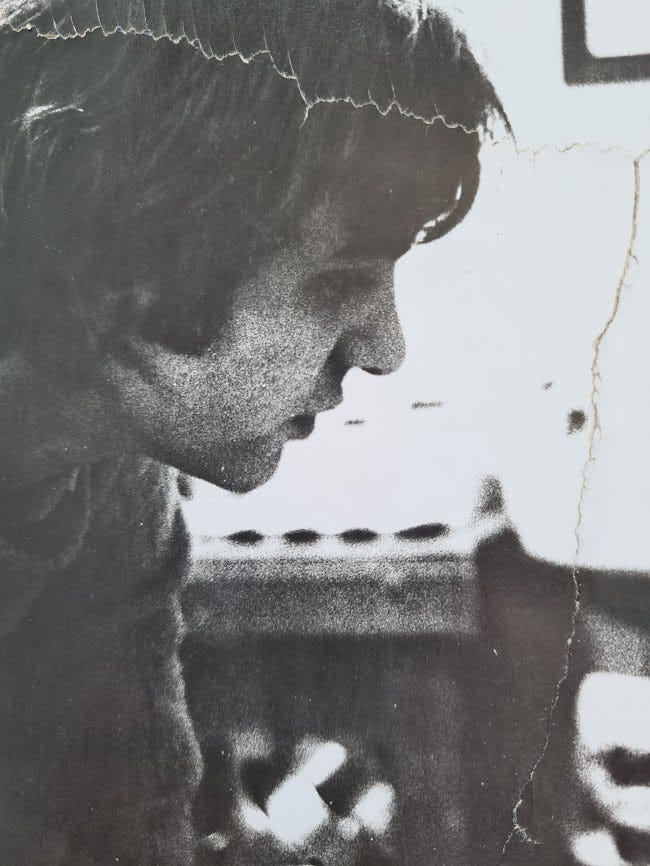

But there is something else here. Do you see that the photo has been torn into five pieces? Here are two of them.

The damage to the print occurred almost exactly a decade later. Ricardo and I both lived on North Street in Northampton at that time but in two different houses. We were bang in the middle of one of our break-ups. Not together, but as was ever our way, not really apart. One hot summer afternoon, feeling hurt and angry about various events and words, I tore up this photo, marched down the street to his house, yanked open his back screen door, and threw the scraps of photo onto his floor.

I didn’t know it at the time, but when Ricardo found the pieces, he gathered them, taped them back together, and pasted the injured print to the card he used for placing his pictures in a ring binder album. Some months later, in better times between us, he returned it to me.

There are many meanings we can make when we hold our old photographs in our hands. But the one that interests me here is this:

Because it has been deliberately damaged, the photograph draws attention to itself as a material object. I am forced to consider it as a piece of paper in time. After it was taken. Its life as a print. My part in its downfall. Ricardo’s part in its rescue. I can trace with my fingertips the rough lines where I tore it, remembering the emotional wildness I experienced that day. It wears this history unashamedly so that I might hold it today and sense the life and times of a single photograph.

At the same time, this stubborn and independent piece of photographic paper carries the image (projected, developed, and fixed upon it) that enables me to catch sight of my own history, his, ours, youth, love, heartbreak, Massachusetts places. I can touch it where the image speaks to me. I can kiss it if I wish. How many of you have kissed the face of a loved one in an old photograph? A mother or father, now gone, perhaps. How often have you been pulled that close to the surface of a photograph, only to realize you can go no further?

Normally, when we look at our old photographs, we “suppress our consciousness of what the photograph is in material terms.” (Geoffrey Batchen, Photography’s Objects, 1997) We say (and here I am borrowing from Roland Barthes), look, this is me. Or, this is my mother. Our house. We don’t say, look, this is a photograph. We forget the photograph’s paperness, its printness, its being-in-an-albumness. We re-enact Barthes’ long-ago insight that the photograph as object becomes invisible because we lose ourselves in the image it carries. This is what he called the “stubbornness of the referent” whereby the print and what it represents, the image itself, are inseparable, “glued together” (Barthes, Camera Lucida, 1980).

And yet, not long after his mother’s death, when the grieving Barthes finally finds the photograph that holds what he calls “the truth of her face”, he begins with the object, the paper/print itself, one in which the image is beginning to fade:

“The photograph was very old. The corners were blunted from having been pasted into an album, the sepia print had faded, and the picture just managed to show two children standing together at the end of a little wooden bridge in a glassed-in conservatory, what was called a Winter Garden in those days.” (Camera Lucida)

From there, he moves towards the image that the paper just manages to show, his mother as a child, and finds in this particular photograph something he could not locate in other pictures of her, something she had “maintained all her life: the assertion of a gentleness… In this little girl’s image, I saw the kindness which had formed her being immediately and forever.”

Elizabeth Edwards argues that Barthes might not have “been so stirred if it had not been for the very materiality of his mother’s photograph. For he yearned to go into the depths of the paper itself, to reach its other side.” (Elizabeth Edwards, “Photographs as Objects of Memory” in M. Kwint, C. Breward & J. Aynsley eds., Material Memories, 1999)

This is true of our most important old photographs. We often experience a painful longing to go into them which is a longing to go back, into the past, recover our younger selves, loved ones who have died, the times and places left behind. We hold the photo in our hands and for a moment, all these losses seem recoverable. The moment passes, as it must. But we will do it again and again, each time we gaze at the photo, pick it up, and hold it to our hearts.

It was 2018. I was moving from one London flat to another. I would not have much space in the new flat and I was determined to lighten my load. Boxes of books went to the local charity shop, as did any clothes that I hadn’t worn in the previous six months or so. In a moment of recklessness that I now regret bitterly, I threw away all my black-and-white negatives. That is story for another day.

The point is: I cannot know whether the negative for this print was among those discarded. But one thing I do know, and it brings a strange comfort, I would not wish to print this photograph again. I have the print I want, baring and bearing its age and its scars.

I look at it now and then. I see its stories. Two young people sit at a kitchen table in the 1970s. Someone takes a photo. Photographer unknown. Print torn and scattered a decade later. Its scraps retrieved and glued back together. Print grown old, yet still an object that passes between the two people, now growing old themselves. They bring differing memories to bear on it.

Do I yearn to go into it? If so, is it the glued version, or the torn pieces? Which of the pieces? Which of its ages do I seek? When in truth, I want them all.

Like always...love it

Another gem, Amy! Thanks for sharing this lovely, thoughtful little story.