“Perhaps a ghost is not something dead, but something not yet born: not something hidden, but something we hope is about to be seen.” (Hilary Mantel)

I recently read Hilary Mantel’s A Memoir My Former Self, a posthumous collection of essays, reviews, memoir pieces, and lectures drawn from four decades of her writing. I can’t say whether Mantel ever read Jacques Derrida’s Spectres of Marx, but she clearly shares his view of ghosts as “those who are not yet born or who are already dead.” (Derrida)

But what is it about this reading, in this current historical moment, that prompted me to watch Mad Men again? Ninety-two episodes over a month or so, right here in 2025. Was it pathetic escapism? A need to commune with ghosts, perhaps? Did the horror of this American moment make an old white girl, born in 1954, long unashamedly for her suburban childhood? All of these, I suppose.

I knew, before I returned to it, that Mad Men was never pure nostalgia. It was, from the get-go, vividly authentic in its visual detail but simultaneously disturbing in its suggestions of unhappiness and inauthenticity. Let’s not forget that its central character, Don Draper, has stolen the identity of a dead soldier. Dishonesty and deception course through Mad Men like a river after heavy rains.

Yet even if it was misplaced escapism, this latest viewing was jarringly unlike the first viewing which unrolled over seven seasons beginning in 2007 and ending in 2015. The era of box sets and streaming was underway, but we still enjoyed that old weekly longing for the next instalment. So, each episode was new. You could say we were innocent viewers insofar as Mad Men’s plotlines and characters were given to us in a slow reveal.

We were innocent, but many of us – the baby boomers, notably – were simultaneously not innocent. We had lived the decade of the sixties. The arrival of Mad Men, with its detailed period restoration and hints of the coming countercultural discontent, served to heighten our prolonged sense of self-importance. For in truth, we had begun mythologizing the period even before it came to an end. Yes, the sixties kids have struggled to get over ourselves, even if this does not always endear us to subsequent generations. No wonder we embraced Mad Men from its very first airing.

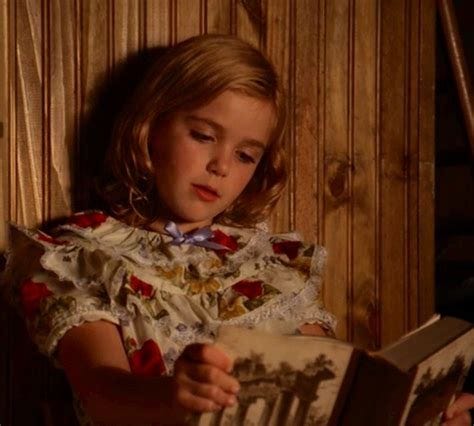

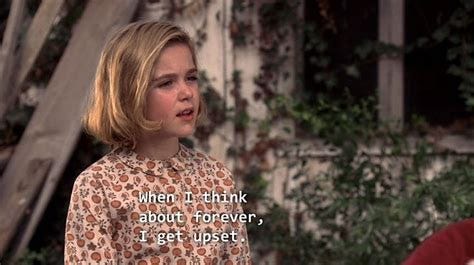

Sally Draper, Mad Men’s central child character, drew particular devotion. Having just passed our 50th birthdays when season one arrived in 2007, we were Sally’s real-life counterparts. Sally was born when we were born. She made us young again. She made the world young again. She tapped straight into our rampant and misguided nostalgia. We could be Sally again, before her (our) future arrived. But Sally, beautifully played by Kiernan Shipka, was also the ghost of ourselves. She could not take away our knowledge of after. If anything, she embodied this dilemma for us: a world of before, forever seen through the lens of after.

Many of us, perhaps the girls especially, tried to fade into Sally and move through childhood as though it were the first time. We might erase the changes and events that we knew, full well, would soon unsettle Sally as they had unsettled us: assassinations, urban unrest, Vietnam, Woodstock, the Manson Family, Kent State. And it was not only these public events that troubled us. As the key domestic space of Mad Men, the Draper household showed the cracks in the suburban picture window, the unease closer to home and in family life. With each season of Mad Men right up to its final episode, we felt for Sally and watched her growing knowledge and disillusionment as though it were our own, because it was our own.

Of course, we could never fade into Sally. We could only be haunted by her. We could only watch her changes from the land of later and after.

If Sally was our ghost of the past, we were Sally’s ghost of the future. It is more likely that she faded into us. And what had become of us? In the year 2015, watching Mad Men’s final series for the first time, we were the ghostly present, the myriad Sallys that the original Sally would become. Her future life up to that moment. Although only ten years away, the year 2025 seemed beyond the horizon, unimaginable. Few Sallys, at any age, could have foreseen 2025.

The Ghost of Bert Cooper: Watching Mad Men in 2025

“In imagination, we chase the dead, shouting, ‘Come back!’ We may suspect that the voices we hear are an echo of our own, and the movement we see is our own shadow. But we sense the dead have a vital force still – they have something to tell us, something we need to understand.” (Hilary Mantel)

Here we are now, ten years on, in the future of the prior future. Time is a crazy and unreliable thing. The bittersweet nostalgia of 2015 has become a Munchian scream of foreboding, a warning called not only to Sally back in the sixties, but to the Sally of 2015. Terrible things are happening here in 2025! And if Sally is us and we are Sally, well… you get the drift. We’re all in deep trouble.

Yes, I still love Sally, identify with her, and tenderly follow her childhood and early adolescence across the seven series. But I feel guilty too. Apologetic. I want to say sorry to her for having become what she will become. An aging white woman in a generation hogging the best of the postwar spoils, withholding these from others, failing to do something about her relative privilege, and effectively enabling the demise of the American Dream. How many of the sixties kids grew up to become Trump voters? I wonder. Dear Sally, I hope you are not one of them. The thought is so disturbing that I run from the ghost of you.

There are three important diegetic ghosts in Mad Men: Don’s brother, Adam (who commits suicide after Don rejects him), Anna Draper (the widow of the soldier whose identity Don has taken), and Bert Cooper (founding member of the advertising agency at the center of the story). The third ghost arrives halfway through the season finale, with Bert Cooper’s death. Bert is the paternal ‘old guard’ of the business right from season one. Two generations before Sally (and her baby boomer viewers), Bert is the age of our grandfathers, long dead even at our first viewings of Mad Men. Other than his interventions in particular key scenes, I have never taken a great deal of interest in Bert’s story or character. He is funny, eccentric, art-loving, but also an Ayn Rand-reading, Nixon-voting capitalist.

Bert’s death comes on July 20, 1969, the night of the moon landing. The episode moves between groups of characters, each watching the lunar landing on television. The generational divides are there. The older ones gaze in wonder; Sally complains about the money spent on space travel rather than more immediate earthbound needs. But when Neil Armstrong sets foot on the lunar surface, the episode is with Bert. As Armstrong speaks his much anticipated first words on the moon, Bert smiles approvingly and utters his last word on Earth. “Bra-vo,” he says, elongating the vowels. We learn that Bert dies in his sleep shortly after the broadcast.

Following his death, Bert Cooper appears twice to Don Draper. The first is a poignant song and dance routine seen only by Don, who enters a fugue as the old man’s death is being announced to the office staff. Bert performs the 1927 song, The Best Things in Life Are Free, written for the Broadway musical Good News. A song with moon references and a counterpoint to the entrepreneurial drive of his long life. It’s almost as if old Bert comes back to tease Don with a previously hidden Bert. A ghost of the ghost, as it were. Let’s face it, we all have them. The ghosts of the people we did not become or, as Mantel puts it, “the ghosts we all have in our lives: the ghosts of possibility, the paths we didn’t take, and the choices we didn’t make…”

Bert haunts Don a second time in the episode titled Lost Horizon, in which Don takes off on one of his periodic ‘runners’. Having walked out of a staff meeting, he gets in his car and heads for the Midwest, apparently to find Diana, a waitress and kindred ‘lost soul’ with whom he had a brief relationship before her disappearance.

Ragged and exhausted after hours at the wheel, Don hears the radio announcer’s voice melt into Bert’s and turns to see the old man in the passenger seat. They hold a brief conversation. Bert recalls an old shop from his youth, a time long before Don, even longer before Sally and ourselves. He reprimands Don for driving in the “wrong direction,” and for liking to “play the stranger.” Don asks Bert if he remembers Kerouac’s On the Road. Bert, having denied ever reading the 1957 beat novel, then speaks its most famous line. And disappears.

Mad Men for 1925. We’re driving in the dark. Here comes an old ghost to ask where we’re headed. Are we ready to say goodbye to summer? Is there something around the bend “about to be seen?” In the night. Something to help us through this present where, as we sixties kids used to say, we gotta keep on keepin’ on. For the future Sallys.