In his address to the joint session of Congress, Trump took ownership of one of our enduring, if conflicted tropes when he declared that “the American dream is surging bigger and better than ever before.”

Cue MAGA chants of U.S.A U.S.A. U.S.A. in the chamber, after which Trump continued: “The American dream is unstoppable, and our country is on the verge of a comeback the likes of which the world has never witnessed and perhaps will never witness again. There's never been anything like it.”

Let’s remember that the American Dream has a history of changing meanings, uses, celebrations, and critiques, most of which have little to do with Trump’s deployment of the term. From the nation’s beginnings, the Dream (in various guises) gave expression to the pursuit of religious and political freedoms, justice and democracy, geographic and social mobility, and the immigrant’s quest for equality of opportunity. Only in its most recent iterations has the Dream become virtually synonymous with the individualistic quest for wealth in which democratic norms and ideals lose out to the demands of millionaires, billionaires, banks, and corporate power.

In her history of two ideas – America First and The American Dream – Sarah Churchwell cites the Progressive Era (late 19th to early 20th century) as a key moment for the Dream, one that would be unrecognizable (and unacceptable) to Trump:

“The “American Dream” really starts off with the Progressive Era. It takes hold as people are talking about reacting to the first Gilded Age when the robber barons are consolidating all this power. You see people saying that a millionaire was a fundamentally un-American concept. It was seen as anti-democratic because it was seen as inherently unequal.

“1931 was when it became a national catchphrase. That was thanks to the historian James Truslow Adams who wrote The Epic of America, in which he was trying to diagnose what had gone wrong with America in the depths of the Great Depression. He said that America had gone wrong in becoming too concerned with material well-being and forgetting the higher dreams and the higher aspiration that the country had been founded on.”[1]

Hardly the stuff of Musk and Trump.

Churchwell then identifies a fundamental recasting of the American Dream during the 1950s whereby it became an idealized vision of consumerism. The Dream was commercialized – success was seen as the capacity to buy. For those of us who grew up in the period, this historic shift would later be dramatized poignantly by the television series Mad Men in which the ad agencies treat even our most intimate quests for happiness as fodder for their campaign slogans and television commercials. Who could forget Don Draper’s casual remark to a potential client, “Oh, you mean love. The reason you haven’t felt it is because it doesn’t exist. What you call love was invented by guys like me, to sell nylons.”[2]

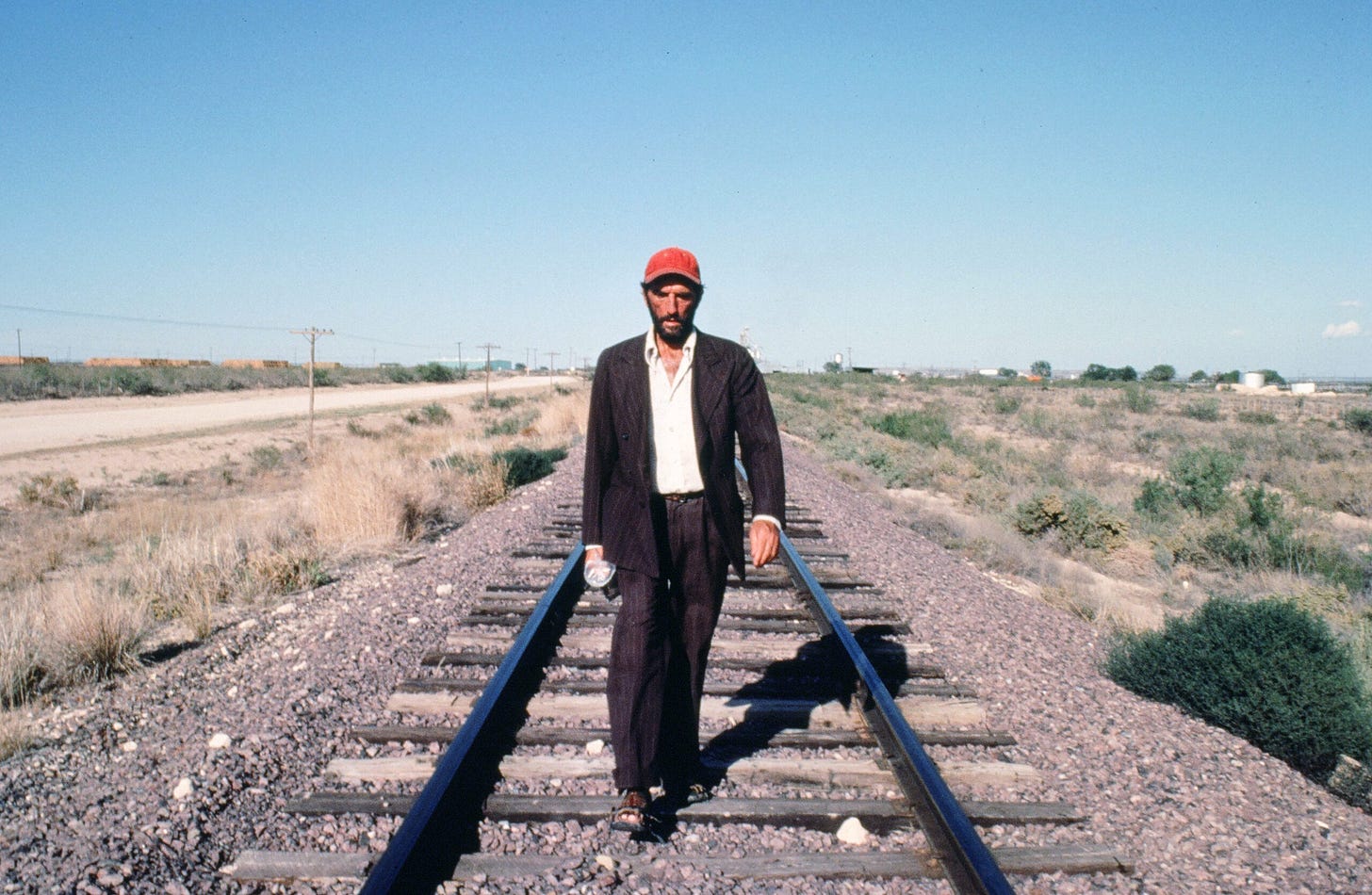

Churchwell further notes that the postwar packaging of the American Dream became a free-market form of “soft power” to be deployed abroad. If, as Fredric Jameson states, the “brief American century” (1945-73) seeded both the fifties dream and its later (sixties) critiques, then the selling of the Dream abroad was a key component. “The Yanks have colonized our subconscious,” remarks a character in Wim Wenders’s German road movie, Kings of the Road (1976). It should come as no surprise that one of the great observers of postwar America was the German filmmaker who would, in his personal experience and art, dramatize the rise and fall of the American Dream from a European perspective:

“Growing up, my idea of America was based on comic strips, rock and roll, movies, and novels. These books, movies, and music revealed to me an alternative culture that I embraced and preferred to my German culture. But of course that didn’t amount to a great knowledge of America.

“And then I eventually traveled here for my first film, Goalies Anxiety At The Penalty Kick that was shot here in New York in ‘72. I lived in the U.S. for altogether 15 years. American counter-culture became a culture I lived in and experienced. I got to know its drawbacks, its eventual failure, but its beauties as well. It became my everyday reality.

“But times changed. The Vietnam War made me look at America more critically, then Reaganomics and the Bush eras. I still love America for what its ideas are about, but I’m also very weary of it. It has nothing to do with what I dreamt of when I was a kid.”[3]

But let’s go back in time again. If Sarah Churchwell justifiably places these shifts in the 1950s, Robert Warshow located their earliest stirrings in the 1930s and the Great Depression. And where did he find his source material? In the classic gangster films of that period. In a 1948 essay predating film studies as a field, Warshow published his seminal essay, The Gangster as Tragic Hero.[4]

In the classic gangster films Little Caesar (1931), The Public Enemy (1931), and Scarface (1932), the gangster is an American dreamer worthy of our attention. He will reach for a slice of the dream, typically behind some enterprising scheme involving bootleg liquor, protection, or a numbers racket.

However, and as Warshow argues, the moneymaking venture itself is given little screen time. It is subsumed in the gangster’s real activity, which is “pure criminality: he hurts people.” This is raw individualism backed by brute force. In other words, as the film progresses, success is defined less by the gangster’s business gains than by the “unlimited possibility of aggression.” It is the American Dream at its most brutal.

Remind you of anyone? Are we not witnessing a gangster presidency? The unelected Elon Musk with his chainsaw and mass firings. A mob-boss president who promises protection for loyalists and punishment for anyone perceived to be disloyal. The ‘dealmaker’ who sees foreign policy as a poker game and a land grab. “You don’t have the cards… you’re either going to make a deal or we’re out,” Trump told Zelensky. At home, the intimidation of journalists and elected politicians who should, at the very least, remember the Dream in its better guises and challenge its latest distortion. The illegal and violent deportations taking place before our eyes. The threats to disappear those who do not fit the white, Christian nationalist blueprint contained in Project 25.

Of course, it would be ridiculous to conflate our current predicament with Warshow’s analysis. Most especially, it should be noted that Warshow was uninterested in examining the real context of Prohibition and the Depression, still less in relating his analysis to any real-life gangsters of the period. For him, this was a question of film-genre conventions and expectations – the “experience of the gangster as an experience of art” universally understood by Americans. For Warshow, the films dramatized a specifically American dilemma, an “intolerable dilemma” according to Warshow: to achieve success, to fulfill the American Dream, we must act with ruthless individualism. The gangster heroes embodied and explored that problem.

Moreover, these were crime-doesn’t-pay stories (made in an increasingly censorious thirties Hollywood), most of which end in the punishment or death of the gangster, for every act of aggression leaves the gangster increasingly alone and guilty. In these rise-and-fall narratives and in the fully anticipated, unavoidable death of the gangster hero, the classic gangster film restored the experience of tragedy to our heavily-prescriptive national culture of optimism. Here then, was a critique of American dream notions of success embedded in the gangster story.

So no, I do not think Warshow’s essay reflects any current reality or provides ideas of how to escape our situation. We cannot hope to find the end of Trumpism in Warshow’s beautifully written lines. But read in full, the essay gives pause. It may, however loosely, suggest how Trump has appealed to Americans for whom the dream has become conflicted or gone unfulfilled. And it may whisper how, and why, many who follow him will eventually come to reject him. A rise and fall narrative indeed.

I find it nearly impossible to feel for those voters. After all, Trump has never hidden his gangsterism. They knew what was coming. They knew that thousands of innocent people would be hurt. They may have failed to see that they too, would be hurt. That realization is coming too. Will it arrive in time to save the republic? We cannot say. The rest of us can only fight Trumpism day by day, remembering that we have all been dreamers of some version of the Dream and, as often as not, its prisoners too.[5] We are, in that sense, together as tragic players in the American story.

[1] Anna Diamond’s interview with Sarah Churchwell for The Smithsonian Magazine. And see Sarah Churchwell, Behold America: The Entangled History of “America First” and “The American Dream” Basic Books, 2018. See also, Jim Cullen, The American Dream: A Short History of an Idea that Shaped a Nation, Oxford UP 2004.

[2] Across seven seasons and 92 episodes (2007-2015), Mad Men remains one of the great period dramas of the postwar period, effectively taking us from the end of the ‘innocent’ fifties to the upheavals of the 1960s, as experienced by Don Draper, his family, and the agency itself. The scene described above can be seen here: The best of MAD MEN 📺 What you call love was invented by guys like me to sell nylons | HD

[3] Wenders has often described his complex relationship with the U.S. The above quote appears in an interview with Ratik Asokan for The New Republic in September 2015.

[4] A link to Warshow’s essay, published by Partisan Review, can be found here.

[5] Mine is a loose borrowing of the phrase. But please do see Mike Davis, Prisoners of the American Dream: Politics and Economy in the History of the U.S. Working Class, Verso Books, 2018. We might recall here too, George Carlin’s remark that “It’s called the American Dream because you have to be asleep to believe it.”

‘A mob-boss president who promises protection for loyalists and punishment for anyone perceived to be disloyal. ‘ So true! Really thought provoking piece of writing.

Mob-bosses are by nature paranoid. They live in a reality where every perceived threat must be extinguished.

Mob-bosses are self-made though, aren’t they. Now, the feeling here in NE, expressed in both hushed or agitated voices, is more like being on a rough sea in a dreadnought, captained by a glory-seeker, hauling us wave by wave into a new uncharted sea. What’s most disconcerting is that the Admirals stand safe on shore, happy to have us sail on to our own peril. I’m halting to think that our only liberation will be in lifeboats.

Or in your analogy, Amy, in the blood of a Broadstreet mob massacre