Son

“Mum, which smile do you like best – one, two, or three?”

Isaac demonstrated smiles one to three and waited for my opinion. I didn’t tell him that there was very little difference between them. All three were small, quiet, slightly shy smiles. I chose number two because I knew it would satisfy him to have an answer, this four-year-old who was thinking about his smile, trying it out before committing it to the world.

The gentle smiles seemed part of Isaac’s gradual emergence from the tantrums and frustrations of his toddler years. In this, he was like many children. I knew this. But I could not escape the feeling that he was a person who would grow happier when his body and mind caught up with his spirit age. When the world caught up. Like George Bailey in that old Frank Capra film, Isaac was, perhaps, born older. This is what I sometimes thought.

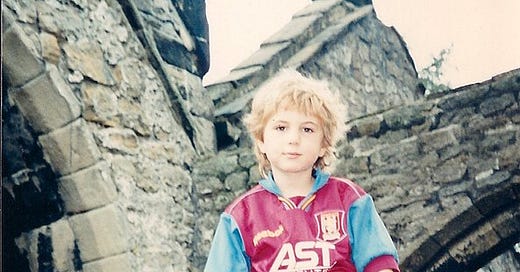

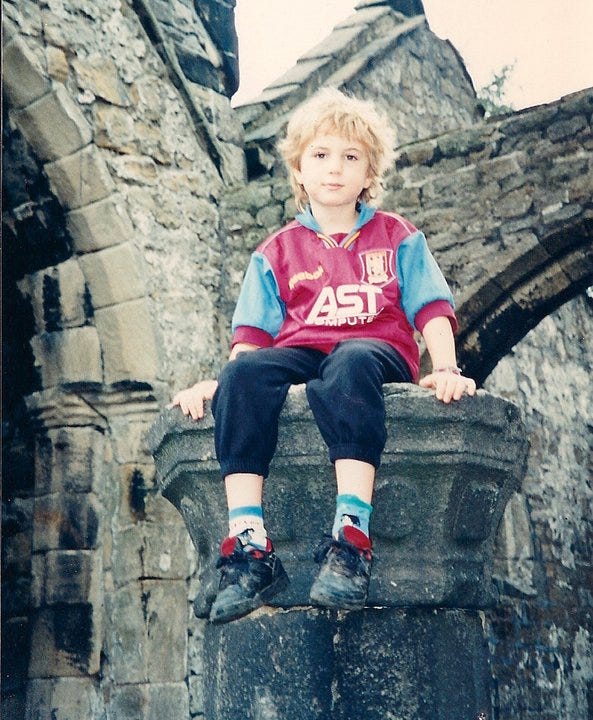

There were random signs from the start. Asking, at the age of five, when he might move to a place of his own. “Where do you want to go?” I asked. “Heptonstall,” he replied definitively. (Heptonstall was the village up the hill from our West Yorkshire home.) His world was still small. I recall thinking this at the time, with some relief. But then he said, “And after Heptonstall, Chicago.” He’d never been to Chicago, but I am a Midwesterner. (At the time of this conversation, we could not know that in later years, Isaac would live in Chicago for a period.)

He learned at an early age to read and tell the time. These achievements seemed to reflect his stubborn desire for personal autonomy, but he was also generous with them. His primary teacher had to ask him to stop repeatedly telling his classmates how many hours and minutes from ‘home-time’ they were. Reading and writing came fast, but Isaac never believed in his childhood artwork. Showing his drawings at school was painful to him because he never thought they were good enough.

From an early age too, he reserved the right to disagree. “It’s so nice today,” I said as we walked to market one warm sunny morning. “No, it isn’t,” said Isaac. He was regularly critical of adult opinion. Equally so of any perceived hypocrisies. School received his most vehement criticism. Having waited for more than a year to receive one of the ‘certificates of merit’ handed out at the weekly assembly, he was unimpressed when finally awarded one. “They only gave it to me because the end of year is coming and I never had one before.”

Isaac was fierce in his first friendships, so when Stella moved away, he was heartbroken. For many months, walking to school, he said he did not want to go there anymore, not without Stella. Isaac’s sense of loyalty eventually carried over to other friendships, as he began to romp with boys, and grew older. As a young adult, his sincere expressions of loyalty would be returned to him. He is a fellow who makes friends carefully and whose close friends stand by him.

There were responses to strangers too – Isaac’s budding personal politics, if you will. For instance, he was still a little boy when we watched a film together, the one about girls in baseball during the Second World War. There is a scene in which one of the characters cannot tell if she has made the team roster because she doesn’t know how to read. When I explained this to Isaac, he cried in rage and disbelief that this should ever be the case.

A few years later, I watched him deliberate long and hard over a Christmas gift for my mother. Far gone with dementia, she had lost language and memory. Finally, he chose a music box that played White Christmas to miniature model skaters on a rotating rink. I watched him help my mother open it and hold her hand as he showed it to her. She let him guide her. He wound the music box for her, keeping his words easy to follow and his voice gentle. It was her last Christmas.

We didn’t know it then, but the little boy with three possible smiles who once asked me which is more important, truth or love, would study philosophy and political theory when he went to university. He grew into a person with questions and curiosity, empathy, a sense of social justice, a guitar, and a love of poetry. These might not always make life easy for him. But they would make it meaningful.

Mother

The parenting of previous generations haunts us as much as it guides us. When my mother died, I thought about how painful it must have been to her that I chose to live an ocean away and rejected many of her wishes for me. I saw her larger story too. That she gave up college for marriage and motherhood. That she devoted years to watching over three children, that she lost a fourth through stillbirth. After she died, it struck me finally that, year by year, she had struggled to let us go. I was the youngest, the last to leave. She witnessed my movement away - toward far places but far thoughts too. At a certain point, you cannot insist that your child cross the street holding your hand and sharing your beliefs, any more than you can turn back the clock. You resign yourself to this moment – when the child walks ahead of you. Differently. And without you.

It is a glad process to behold the gathering character and independence of our son or daughter, but it also carries this sense of loss. I didn’t think about any of it until my mother died.

Letters

Mine was the last generation to conduct most of its long-distance relationships through letters. I was slow to answer letters from my mother. It was both sad and fortuitous that I happened to be reading Jacob’s Room around the time of her death, a novel in which letters figure evocatively, including those between mother and son:

“Meanwhile, poor Betty Flanders's letter, having caught the second post, lay on the hall table—poor Betty Flanders writing her son's name, Jacob Alan Flanders, as mothers do, and the ink pale, profuse, suggesting how mothers down at Scarborough scribble over the fire with their feet on the fender, when tea's cleared away, and can never, never say, whatever it may be - probably this - come back, come back, come back to me… But she said nothing of the kind.” (Virginia Woolf, Jacob’s Room)

In her later years, when my mother was just beginning to lose language, before we knew fully of her diagnosis, I received a letter from her that surprised me. Rather than the resolute cheerfulness and platitudes about family love that characterized most of her cards and letters, she apologized (in handwriting grown shaky) for not understanding me, for having struggled to recognize my ideas and aspirations. “I shall always feel that I could have done better,” she said. And finally, with little spelling mistakes she would not have made before, she wrote, “I find myself not [wandinting] the years to go [buy] for fear I won’t see you forever.” And at the bottom of the letter: “Your mom doesn’t write as well as she [yused] to so forgive mistakes.”

“Ah… when the post knocks and the letter comes always the miracle seems repeated—speech attempted. Venerable are letters, infinitely brave, forlorn, and lost.” (Jacob’s Room)

I saw that my mother was worried about words spoken in the past. But also, about words that had not been spoken. Mostly, she was worried about losing words entirely. She was looking back. She was referring obliquely to heated arguments between us during my adolescent years when I was agitating for independence and the right to choices that she could not recognize from her own coming-of-age. To me, when her letter arrived, it was no longer needed. The battles had been fought and if anything, I had come to feel, as a young mother myself, that I had been too hard on her and had failed to understand the fervour of maternal love.

I phoned her and said she had no cause to feel sorry. I had always felt loved, even when we disagreed. And I loved her in return and always would. I remember she said, “Amy, I wish I could see you teach one day at the university.” This opportunity never arose as she did not make it over to England again. At the time, I found the idea slightly embarrassing, but I realize now that she was expressing something most mothers come to feel – a longing to see our child with our lenses removed, lenses tinted by motherhood itself. To see our children unfiltered by our gaze and freed from our gaze too. Our children as free agents, not altering their words and deeds to accommodate the presence of a parent. And to see them through the eyes of others. The not-mothers. Friends, workmates, and strangers.

A few years ago, there was a film in which a mother said to one of her son’s friends, “You get to see him out in the world, as a person. I never will.” The friend shows the mother a photograph of the son dancing, eyes closed, trancelike, in a music club. The mother looks at it, smiles slightly, then turns away. I realized that was all my mother was asking when she said she would like to see me teach. It was a humble, forlorn request that even if met would not have delivered her deeper wish. Because in that lecture hall, we would still be mother and daughter.

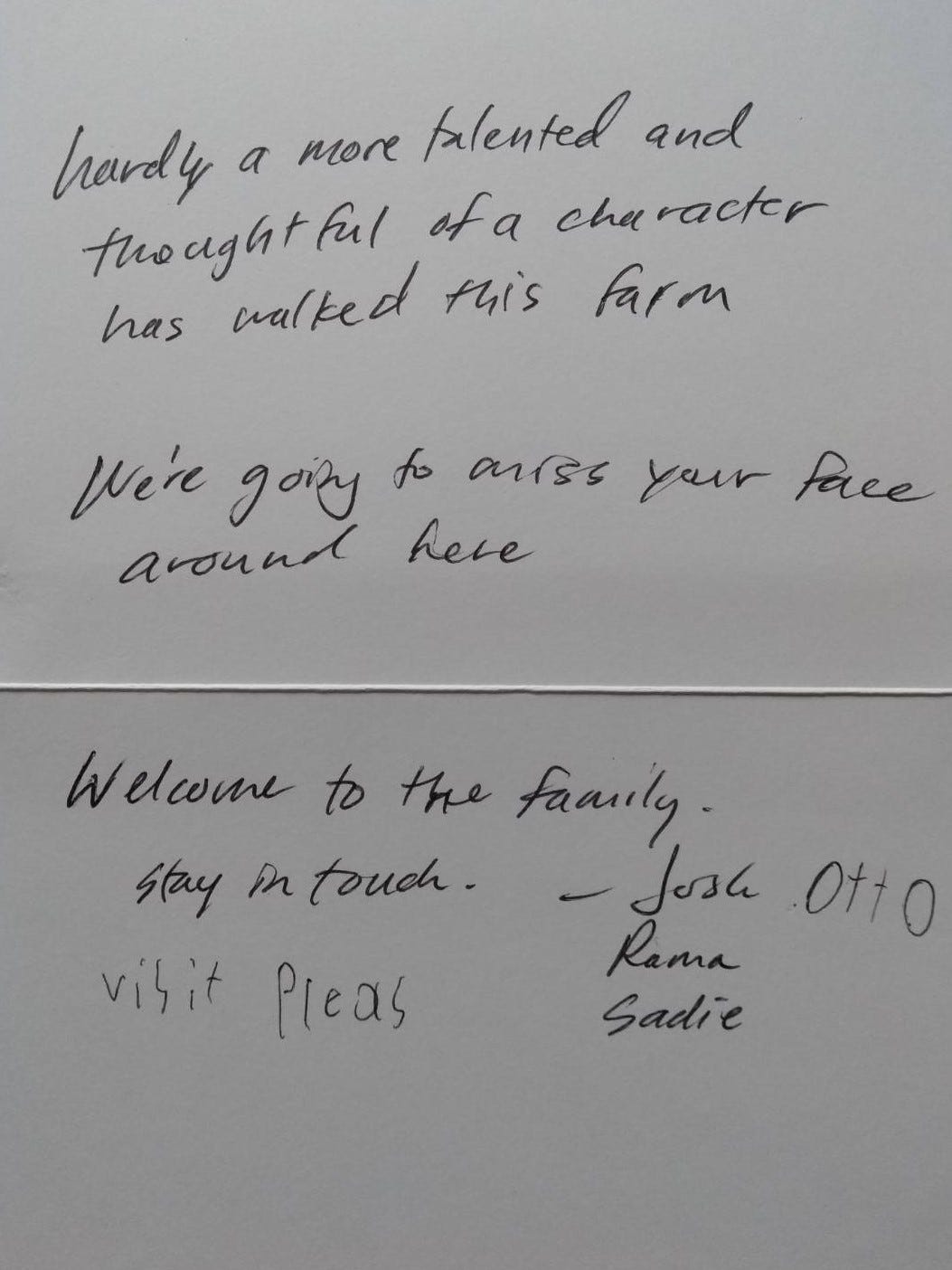

But yes. If we are lucky, we do catch tiny glimpses of our children when they are away from us. Grown, independent, and seen through the eyes of others. I caught one recently. And funnily enough, it took the form of a handwritten note given to Isaac. In America, Isaac spent a season working on a sustainable farm in Wisconsin. From spring planting to harvest, a long-held dream. At the end of his time there, as Isaac was about to drive away, he found a card left on his car seat by the farmer and his family.

There he was, the boy with the three gentle smiles, choosing for himself. Finding his goodness and taking it to the world.

With thanks to Isaac for generously sharing this, and much else

You should know I love your writing. I find it a hard read because we are now our mothers. I myself am now my Grandmother. Our lives are coming to it’s conclusion sooner then we’d wish. My mother is still here in this world fighting for every day. You keep writing and I for one will keep reading.

Oh Amy, tears are streaming down my face. So relatable, and you’re such a gifted writer. Thank you for this. Today my daughter is driving back to college and her “other life”, and I’m feeling it all…