“That people could come into the world in a place they could not at first even name and had never known before; and that out of a nameless and unknown place they could grow and move around in it until its name they knew and called with love, and call it home, and put roots there and love others there; so that whenever they left this place they would sing homesick songs about it and write poems of yearning for it, like a lover…” (William Goyen, The House of Breath, 1950)

We move from one home to another. Some of us, many times during our years. Some only a few times. Perhaps a very few of us, never. The causes and reasons for staying and leaving are many. Necessity, desire, an innate restlessness, or a confusion of all of these. Sometimes, it is the road one longs for, transience rather than a stopping place/time. But whatever moves us to move, we carry our causes and reasons with us. Each move poses old questions, like a gust of warm wind kicking our dust again. We confront the meanings we have given to home as an idea, and to the places that have been homes, for these are not the same. We set ourselves the task of making them the same, with unforeseeable futures. And we wonder which of our past locations we might always call home, whether we reside there or not, whether we have loved them or not. There may only be one such location or there may be many. For me, I realize, there are many - an outcome that brings both adventure and comfort, but a measure of grief too.

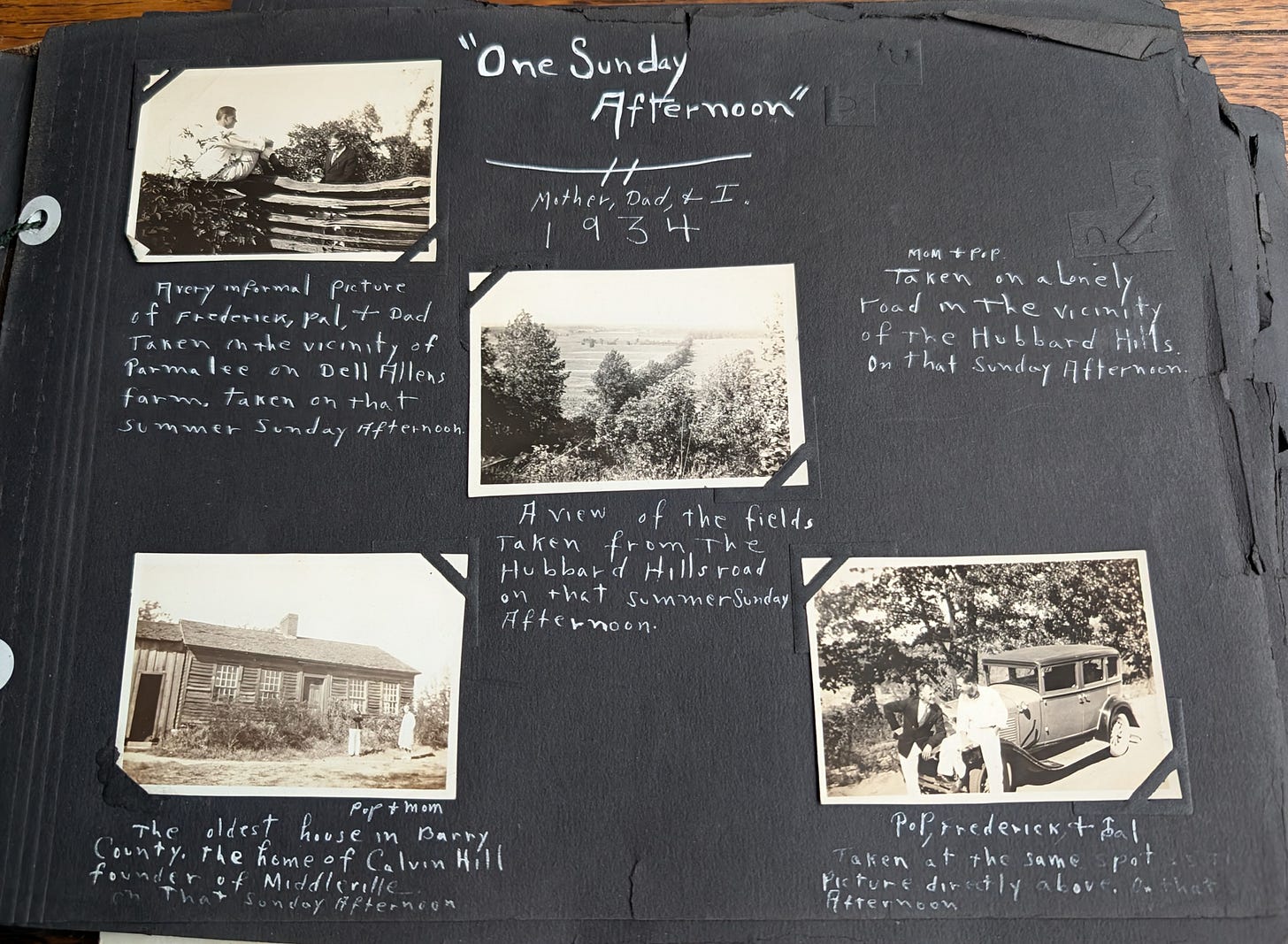

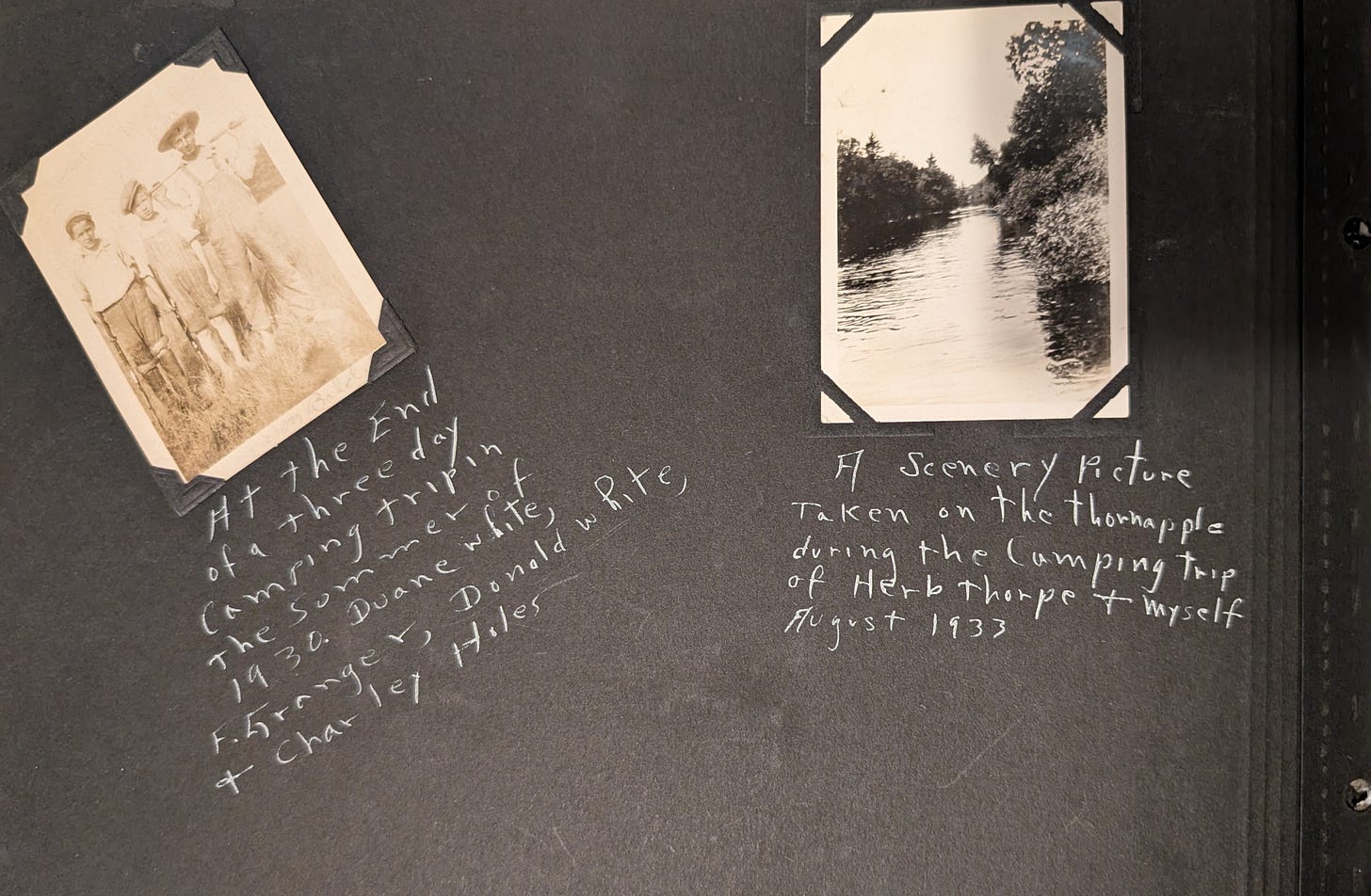

But a new question arises as the years go by. It concerns the meanings others have given to home, most notably our parents, grandparents, and ancestors whose artifacts we may now carry together with our own. Here is a photo album that dates from the 1930s:

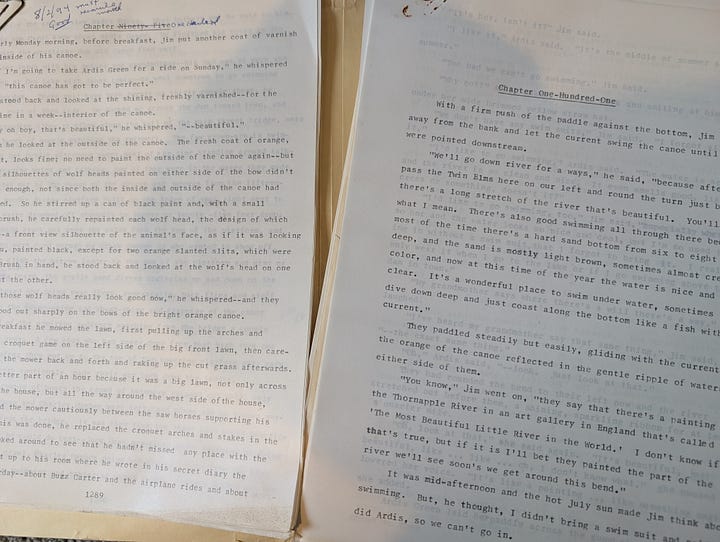

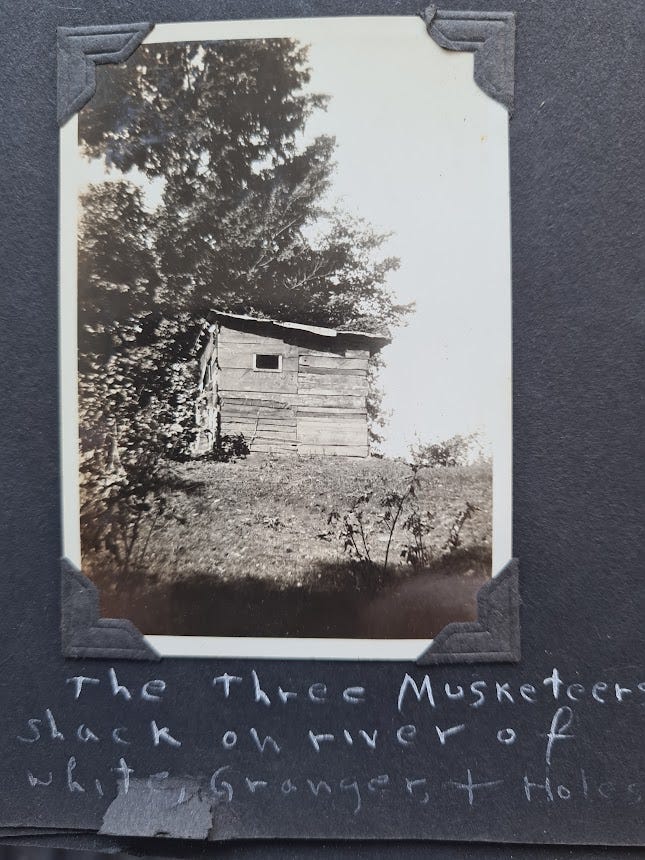

The album was created by my uncle, Frederick Granger, during his youth in Middleville, Michigan. The album, together with his unpublished novel (written when he was an older man) came into my possession after he died in the 1990s. Titled The Search for Heart’s Hold, I have read most of the weighty manuscript, its chapters running into the hundreds, and thanked my departed uncle for unlocking a door to the boy’s childhood in the hometown he shared with my mother. She is there too, though this is more Huckleberry Finn than Little Women or Little House in the Big Woods.

I have transported the photo album and accompanying manuscript from one home to the next, wondering always what to do. The freedom of boys runs through them. Weather and the seasons frame Fred’s eye and storytelling. The town is ever-present in its people, its Main Street shops, old hotel, school, river and trails, Parmalee Cemetery where the ancestors are buried, and finally, in the boys’ pranks and ventures many of which must be thinly-veiled incidents re-imagined by my uncle.

Dear old Fred needed a good editor, as we all do. He needed an editor to insist on… well, telling the story a bit quicker and cleaner. He might have accepted an editor who knew the place as he did. But then, none of us have such luxury when we write. I tried many times to put on an editor’s cap, but Fred was too close. He was over my shoulder, stubborn and opinionated. He did not wish me to violate his work. We cannot be cruel, even cruel-to-be-kind, to those we love. And I loved him.

I loved Fred and I could never grasp Middleville, Michigan as he and my mother did. Although I visited the town regularly during childhood, it was not mine. Yet each time I leaf through Fred’s photo album or the pages of his manuscript, I experience the force of something that has passed into me. It’s a ghostly pre-history to my history. And I experience, could it be, an unfathomable bout of homesickness. I have asked this question elsewhere, but I ask it again here: can we be homesick for places that are not our home?

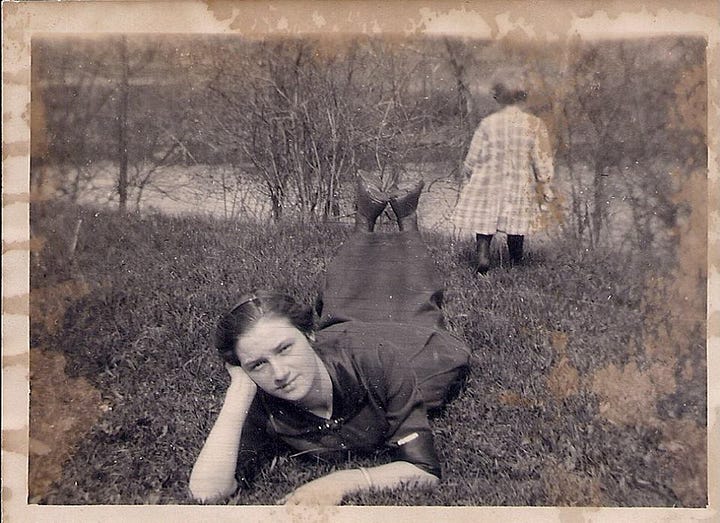

The feeling may be partly explained by family ties, the simple presence of my mother and grandparents in the album, yet it stalks me when I leaf through the other pages in the album, seeing not only pictures of family but scenes without people - the Thornapple River, farmhouses, dirt roads, an old gas station. The photo album, from its ancestral faces to lonely roads covered in snow, seems to provoke a referred homesickness in me. Not only am I doomed to miss my own hometown; it seems I miss my mother’s hometown.

Opening the album, I make my return.

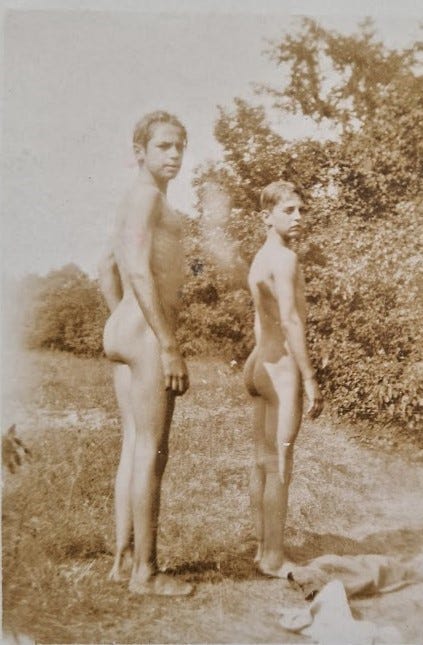

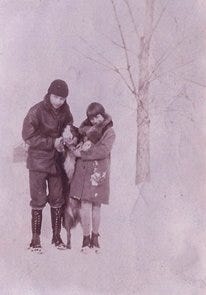

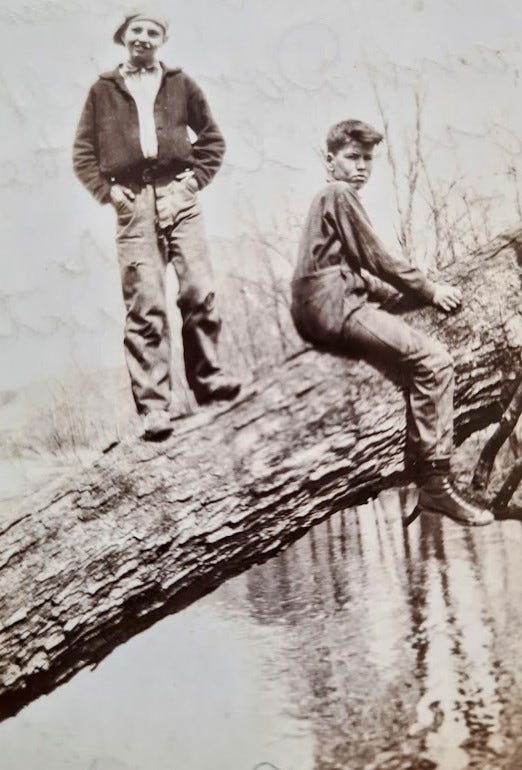

Thornapple River, with the boys

“For we are where we are not,” it seems. (Pierre-Jean Jouve, Lyrique)

“Something unreal seeps into… the recollections that are on the borderline between our own personal history and an indefinite pre-history, in the exact place where… a childhood home comes to life... For before us, it was quite anonymous. It was a place that was lost in the world.” (Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, 1958)

There are places and words that we love, often inexplicably, and so we say them aloud to empty rooms or while out walking. For the mystery and pleasure of their company. “Michigan,” I might say to the word. “I find your very name to be a dark and beautiful holder of secrets. May I invite you into this sentence I am writing?”

“Thornapple River,” I might say to the words, “Will you join my sentences too? Will I come back to you one day? Might I climb a tree and look down into your waters? Might I swim in the wild with you, then scramble up the bank to the shack, the hideout?”

The old shack where boys’ meetings were held and plots were hatched, might be the home Fred remembered most when he wrote his novel as an old man. Might I go there too? For “who has not deep in his heart / A dark castle of Elsinore?” (Vincent Monteiro)

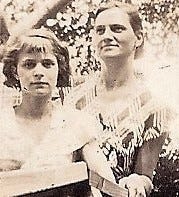

Fred’s sister, my mother

Look upon the face of any person and you may glimpse, without knowing, all their ages inscribed there. Part of remembering our parents is to sense – rather than know – the presence and persistence of earlier lives in the two people as we found them, later. I am in the habit of sniffing a near-empty bottle of cologne that my mother left behind. I hold it close to my face and breathe in Shirley Granger. My mother’s physical presence is a scent now, rather than flesh and blood. But in that scent, she visits. In Fred’s photo album, she visits.

Think about the imbalance our parents face. They see us from our earliest moment when we open our infant eyes to the coming confusion of life. If they are lucky in later years, our parents will guard that memory as precious. If we are lucky, we will have our parents to remember us for as long as possible. They will get us wrong sometimes, but the history is there. “I knew you first!” our mothers might say. But think now, in reverse. We never saw our mothers and fathers when they were children. We never will. This is not something we can give them, much as they might long for it.

I can’t help but wonder if my mother sometimes lamented this ‘lag’ of parenthood: that children arrive halfway through one’s history. That our children cannot visit our early years to understand the forces that shaped us.

I am looking at my mother with her mother before they died and after they died. I see a land of before from the land of after. I see my face in my mother’s face. She looks back at me, catching sight of how her girlish face will age. Our eyes meet for an instant. Then she is gone, though I hold the moldering print in my hands. Unable to reach her or know her as a child, I take hope from Richard Ford’s read of this parent-child imbalance.

“Incomplete understanding of our parents’ lives is not a condition of their lives. Only ours. If anything, to realize you know less than all is respectful, since children narrow the frame of everything they’re a part of. Whereas being ignorant or only able to speculate about another’s life frees that life to be more truly what it was.”

“Our parents’ lives, even those enfolded in obscurity, offer us our first, strong assurance that human events have consequences. Here we are, after all.”

“The future is unpredictable and hazardous, but our parents’ lives both enact us and help distinguish us. My own belief in life’s final lack of transcendence always turns me to thoughts of my parents. In difficult moments, long after their deaths, I often experience the purest longing for them – for their actuality.” (Richard Ford, Between Them: Remembering My Parents, 2017)

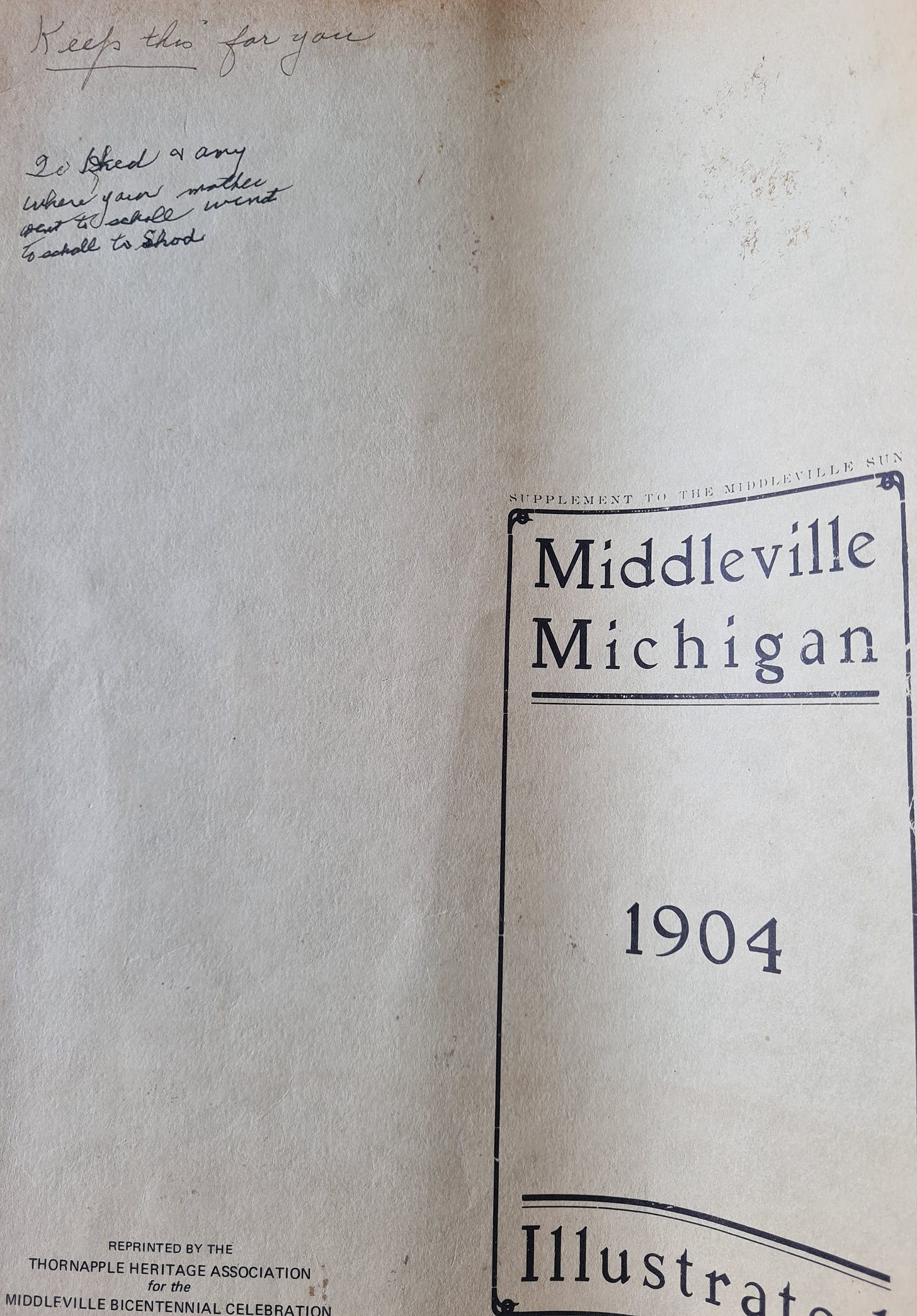

From the brink of her dementia in later years, my mother sent me this commemorative booklet produced by the local heritage association. Struggling to find words, losing the ability to spell the words she could find, she tried to draw my attention to her lingering memories. On the cover, determined to tell me that Middleville was where she went to school, she made three attempts to spell the word, never quite managing it, but these efforts signaled its importance to her.

I wish I could tell my mother that I regularly look at her childhood photos and I pull out that old commemorative edition of the Middleville Sun newspaper with her imperiled words scratched in the margins. I cannot hold her early life in my memories, but I can hold her late-in-life desire to hold it for herself, and her labored efforts to communicate it to me.

All the people in Fred’s photo album are gone now. I am moving. Bringing them with me. Thinking about my homes. Their homes. Our homes. And for a dreamlike moment, going back to Michigan. Mich-again, again and again.

beautiful Amy...Love the thought of Fred's album witnessing the making of new memories in Brighton. ❤️

Once again, your words have such an impact on me. I find myself smiling as I imagine scenes from my mother’s childhood. Then a few paragraphs later a tear falls from my eyes, as my actual memories of her come to mind. I’m so glad you share, Amy! And how wonderful it is that you have these tangible items of history. 🩷 I hope your upcoming move is good for you!