The early photographers worked with available light, so the advent of flash would cause some debate about the aesthetic integrity of artificial illumination. But once it became a thought/invention, rather like photography itself, flash could not be extinguished. It began as an ornate and often dangerous effort to take photography, which means ‘writing with light’, to places where light could not be found. Interiors. Caves. Tunnels. Corners. Night.

The earliest known flash photography dates from 1839 and was produced by limelight. In a process borrowed from theatres and music halls, a ball of calcium carbonate would be heated in an oxygen flame until it became incandescent. By the 1860s, magnesium served as the principal source of illumination, but as Kate Flint (a historian of flash photography) notes, flash retained an “explosive unpredictability.” Even after 1887, when Johannes Gaedicke and Adolf Miethe invented a more reliable compound – Blitzlichtpulver (lightning flash powder) photographers suffered frequent burns and injuries, while studio explosions and fires continued to be a hazard of the profession.

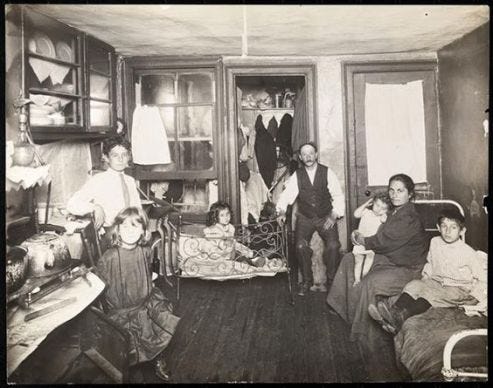

Simultaneous to these practical obstacles, flash prompted moral and aesthetic debate. On the latter point, was it a perversion of photography itself? A violation of truths that might only be reached in natural or available light? Was truth compromised by such contraptions? Or – and here we cross to the moral and political concerns – was flash both the means and metaphor for shedding light on hidden worlds, showing us our dark corners? Certainly, this was the intention of Jacob Riis, who deployed flash in his Lower East Side tenement photos taken in the 1880s and 1890s.

In the decades after Riis, the question of flash as productive intervention versus flash-as-violation would divide the documentarians, including the Depression-era, Farm Security Administration (FSA) photographers. Dorothea Lange, who disliked the intrusiveness of flash, took her best photographs outdoors. Ben Shahn declared flash immoral, noting that it destroyed the real darkness of the sharecropper’s cabin: “I wanted very much to hold onto this [darkness] you see. Now, that’s a matter of personal judgment… whether you divulge everything or whether things are kept mysterious as they are viewed.” (Flint, Flash!: Photography, Writing, and Surprising Illumination, Oxford UP, 2017.

Yet other FSA photographers – most notably Russell Lee and Marion Post Wolcott openly incorporated their use of flash, while Flint notes that Walker Evans was more circumspect, reported by James Agee to have reversed a tiny mirror so that the flash might not be reflected back in one of his interiors. (See Flint, Flash!)

The FSA photographers had access to flashbulbs, which replaced the old powder solutions and were generally available after 1930. The “ease and portability” (Flint) of the bulbs would have an impact not only on documentarians, but on police and news photographers, and those later termed the paparazzi (after the photographer-character named Paparazzo in Fellini’s 1959 film, La Dolce Vita).

Weegee’s crime photographs (1930s and ’40s) would find their counterparts in the pulp fiction novels and films of the period. George Harmon Coxe’s character, Flashgun Casey, was a crime photographer who first appeared in a 1934 edition of Black Mask, the influential pulp magazine, before featuring in novels, radio, television and film.

Cinema has featured numerous memorable photographers from the very beginning, but none used flash as deliberately as Hitchcock in Rear Window (1954), when Jimmy Stewart’s wheelchair-bound photographer uses his flashgun to disorient the killer. We are shown each flash as the photographer covers his own eyes before setting it off, but then we switch to the reverse angle, seeing the flash through the eyes of the killer, as his retina is overwhelmed and his vision floods with red.

Yet what Flint calls the “drama of flash” – its high contrast, “intense darkness” against bright light – is perhaps best considered in relation to forties film noir. Noir replicated that high contrast imagery, but in fact, its visual effects typically derived from low-budget (and therefore low-light) B-movie cinematography. In addition, film noir emerged in the decade suffused with darkness, post-war malaise, and pessimism. It was a cinema marked by altered gender relations, the arrival of German exiles in Hollywood, and the legacy of German Expressionism.

These were the cultural shadows embraced by noir and which ran counter to flash photography’s metaphors of clarity, (E)nlightenment, and revelation. So if noir draws at all from metaphors of revelation, this is to be found in its narrative structures, particularly its regular use of flashback, rather than its cinematography.

Next up: flashback