“It’s nice, but where is God?”

Yes, it was a child’s first church attendance and a forgotten question (later recounted back to me) that privileged sight over the other senses. If I couldn’t see the guy, well then! No satisfactory answer or proof seemed forthcoming and so, Sunday after Sunday, my hopes for some visual confirmation of God’s existence faded. But for a year or two, I believed in the church of Big Boy diner and attended Sunday sermons willingly because after each sermon, we drove to Big Boy for a family meal. This was, you might say, the fast-food compromise of a postwar suburban girl as yet lacking the lexicon of belief and unbelief. Plus, the chocolate milkshakes were delicious. Big Boy was the god of milkshakes. I became a believer.

Imagine then, the creative possibilities carried upon the gust of wind that tore into the town of Kalkaska, Michigan in 2018 to bring down the local Big Boy figure. I was all grown up by then and an ocean away, but it was as if a last god had been toppled. I knew, by then, that this was a different kind of god, better explained by Marx than the Bible. But anyway, a god toppled is always something to ponder.

During the next year or so, I returned to this small episode of Big Boy history again and again, trying but failing to turn it into an amusing story. Along the way, I read into the history of Kalkaska County and northern Michigan. Kalkaska is located in the territory once known as the Council of the Three Fires, an alliance between the Ojibway, Ottawa, and Potawatomi native peoples. One idea for a story concerned a group of scrappy women who, after the storm, began gathering beneath the fallen Big Boy to complain about their husbands. This came to me after I happened upon the Water Spider story as passed down in oral tradition and known under many titles, including Grandmother Spider Steals the Fire and Grandmother Spider Brings the Light.[1] I would lend my characters the powers of Grandmother Spider. I would make the fallen Big Boy of Kalkaska a site of pilgrimage for wise, but grumpy women and aging feminists across the nation.

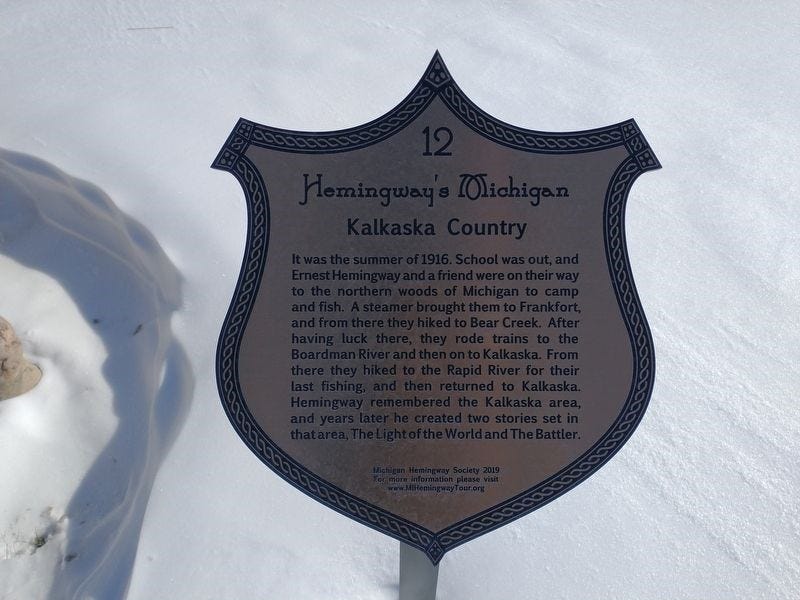

I read on, learning about white settlement in the county, the displacements of the old tribes, local trails, forests and towns, trout fishing, hunting, and Ernest Hemingway’s passages through the region. I found the locations of commemorative plaques to many of these histories, including this one to Hemingway and the two stories he set there. I decided to read more Hemingway but as one of my characters, one of the scrappy women in my story. What would she make of old Hemingway? But that didn’t happen.

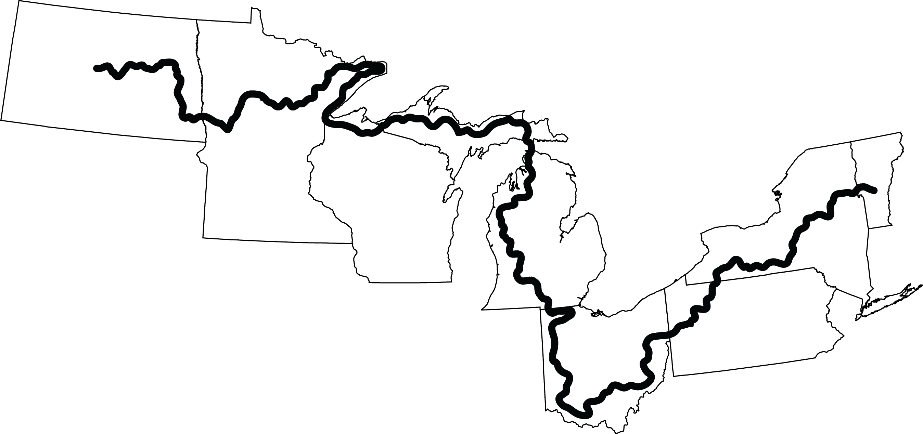

Then, I dreamed of walking the North Country Trail from east to west, in and out of Kalkaska, passing the fallen Big Boy monument, and heading north for the Upper Peninsula and Minnesota, where I might sing Dylan songs about history, the Great Lakes and North Country people.

Thought I'd shaken the wonder and the phantoms of my youth

Rainy days on the Great Lakes, walkin' the hills of old Duluth.

There was me and Danny Lopez, cold eyes, black night and then there was Ruth

Something there is about you that brings back a long-forgotten truth.Something There is About You (Bob Dylan, Planet Waves, 1974) [2]

Well, I guess you’ve figured out that I never did write the story of the scrappy women of Kalkaska. Nor did I walk the North Country Trail, though I did sing a lot of Dylan songs while dreaming about the Trail.

But the Kalkaska Big Boy continued to evoke early memories of church and childhood. However much the fallen monument intrigued me, I realized that the intrigue concerned my earliest exposure to religion and questions of faith, to ideas rather than milkshakes. My intrigue had to do with remembered innocence and the reluctance of children to be persuaded or governed by adults. Eventually, we moved to another town and stopped going to Big Boy for Sunday meals so, at the first opportunity, I stopped going to church.

It would be some years before I realized that many, far more thoughtful unbelievers had gone before me. The most initially helpful among these would be George Eliot (Marian Evans, 1819-1880) whose novels invariably featured religious characters, some wrestling with questions of faith, some not.

Upon losing her faith, the young Marian struck a compromise with her devout father: she would attend Church but must be allowed to think what she wished while there. In 1854, she translated Ludwig Feuerbach’s The Essence of Christianity (1841), which (in simple terms) argued that God is not an external reality but humanity’s projection of its own desire and capacity for goodness. In other words, what we have created, in God, is an image of our best selves, an image that we have made and externalized.

George Eliot retained a lifelong (and not unsympathetic) interest in the effect of religion on individual lives, without wavering from her renunciation of it. W.H. Mallock (a contemporary reviewer) would describe her as England’s “first great godless writer of fiction.” Yet Eliot’s novels often gave us heroes and heroines who, with or without religious faith, sought to do good in their immediate worlds. In Middlemarch (1871), Dorothea Brooke tells Will Ladislaw,

"I have a belief of my own, and it comforts me. […] That by desiring what is perfectly good, even when we don't quite know what it is and cannot do what we would, we are part of the divine power against evil – widening the skirts of light and making the struggle with darkness narrower… What do we live for, if not to make life less difficult for each other?"

Dorothea would become the greatest of Eliot’s morally earnest and authentic characters, and the novel is in many respects an affirmation of such beings, many of whom are women whose opportunities to act upon the world are narrowed and whose histories are lost:

“Feeling that there was always something better which she might have done if she had only been better and known better, her full nature spent itself in deeds which left no great name on the earth, but the effect of her being on those around her was incalculable... for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.” (Middlemarch)

I seem to need George Eliot these days because life, and my thoughts about life, have been much taken up by this question of goodness. It’s been a hard year of loss, change, and worry about the future. Where will I be? How and where, as I approach the age of 70, should I live? Amid intractable uncertainty about my living situation, I took the most painful decision of all my years when I gave up Gladys, my beloved Spaniel. For readers who were unaware, the sad story is told here: Loyalty in Twelve Pieces. As things have played out, I can see that it was probably the only decision I could take, but this does not automatically translate into forgiveness of myself.

There is not a day that passes when I don’t think about her, cry over her, and blame myself. This does not mean there is no joy or laughter. Not at all. But it does mean that the story of Gladys runs through me now. I cannot shake the feeling that having given up Gladys, I will not fully recover whatever humble belief in my own ‘goodness’ I might have possessed before this hard year. And the truth is I don’t want to hide from such thoughts, because that would be to truly lose her.

Once in a while, it crosses my mind that faith in God might come in handy at times such as these. But faith there is not. There is, however, the helpful George Eliotian question of goodness, what it means to be a good person. The knowledge that we humans live with our bad while trying to make good. It is possible and desirable to hold these things together. Just maybe, that is how we make good.

So, welcome to Monday morning. Gods and big boys may be toppled to reveal the trickier question of goodness. If I need words to help me along, I might just curl up with my old copy of Middlemarch and commune with Dorothea for an hour or two. Then play a little Dylan. Then think about Tuesday.

[1] See Indigenous People’s Literature for one version of Grandmother Spider and The First Fire.

[2] See North Country Trail for more dreamings.